<TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=yspsctnhdln>Scout's honor</TD></TR><TR><TD height=7><SPACER height="1" width="1" type="block"></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD>By Jeff Passan, Yahoo! Sports

July 7, 2006

<TABLE id=ysparticleheadshot cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 align=left border=0 vspace="5" hspace="5"><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=3 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=2 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD> </TD></TR><TR><TD>

</TD></TR><TR><TD>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>The sound of twisting metal woke up the whole neighborhood. There had been a nasty accident. A 16-year-old fussing with the radio lost control of his car, crashed into a parked one and thrust it into the next driveway. The kid was OK, just nervous that the guy whose car he destroyed might kill him.

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>The sound of twisting metal woke up the whole neighborhood. There had been a nasty accident. A 16-year-old fussing with the radio lost control of his car, crashed into a parked one and thrust it into the next driveway. The kid was OK, just nervous that the guy whose car he destroyed might kill him.

Brian Wilson, Cincinnati Reds scout, husband, father of three girls, pig farmer and, in this case, vehicle owner, emerged from the house. He was staying with Jimmy Gonzales, his good friend and also a Reds scout, and rather than survey the damage with narrowed and angry eyes, he walked to the car and emptied it.

"He knew it was totaled," Gonzales says. "So he got his stuff out of his car. His car was dirty, too. Things everywhere. In the back, he had a bunch of Reds hats. And with everybody outside, at 6:30 in the morning, he started passing out Reds hats. To the neighbors. To the cops. He gave one to the kid."

Scouts are the traveling salesmen of baseball, sentenced to lives on the road and overworked odometers. They are also the nurses, eminently underappreciated, and the teachers, terribly underpaid. And that is why when Brian Wilson, 33 years old, died of a heart attack on June 17, the news was relegated to a two-sentence blurb.

Paring Wilson's life down <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

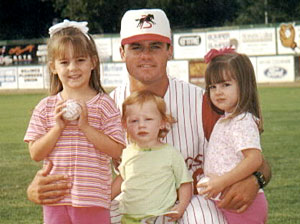

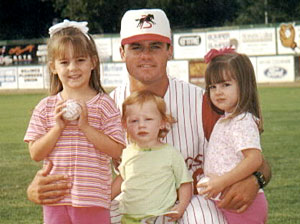

<SMALL>Back row: Brian Wilson and his wife, Prairie. Front row: daughters Conor, 10; Carson, 12; and Curry, 8.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>to a handful of words was like whittling a Sequoia into a walking stick. For the last 10 years, he worked his way up from area scout to supervisor for all of Texas. He signed the Reds' last two first-round picks, outfielders Jay Bruce and Drew Stubbs. He was Willy, parent-charmer and joke-teller, the walking compound adjective.

"He was the backbone of our scouting department," Gonzales says. "He wasn't just one of the veterans. He was the best evaluator, not even close, and he was as hard a worker, as far as production."

In Albany, Texas, the town of 1,900 where he grew up and lived, he was Brian. Whose daughters, Carson, 12, Conor, 10, and Curry, 8, let him clip and paint their toenails, because he was afraid their mom, Prairie, wouldn't do it right. Whose nose – protruding some might say, big and beautiful he'd contend – forced him to turn a soda can sideways if he wanted to drink it. Whose absent-mindedness seemed to lead his sunglasses astray, until someone pointed out they were resting atop his head, which would prompt him to say, "Hey, I'm just a redneck from West Texas."

For a redneck from West Texas, he gave good advice, and so friends and peers sought him out often to hear his simple wisdom. Two weeks before Wilson died, he got a call from Tyler Wilt, a scout with the Reds out of Chicago. He was Wilt's best friend, though a lot of people say that about Wilson. He helped Wilt ascend from a birddog in Texas to an integral part of the Reds' operations in the Midwest, and Wilt, suffering from a temporary bout with confidence, needed some reassurance.

"Don't let this job get to you," Wilson said. "If you have a heart attack and die, they'll just move on and give the job to someone else."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

One summer, Brian Wilson lived in the press box at Hays Field at Lubbock Christian College. It was 1991, and an injury forced him out of the summer Jayhawk League. He didn't want to go home to Albany, and the 750-seat stadium sat empty during the summer, so Wilson plopped a bed in the radio booth and hooked up a TV in the adjoining room.

"Cribs" it wasn't.

"But Brian was like Tom Sawyer painting the fence," Wilt says. "He made it sound so good. I was living in a four-bedroom house with my parents, and I was like, 'Boy, I wish I could live in a press box.' "

Born in Graham, Texas, Wilson moved an hour Southwest to Albany while in first grade. His mother, Vickie, was an English teacher, and his father, Carl, taught agriculture. And Wilson was the small-town jock incarnate: the football and baseball star who dated the captain of the cheerleading squad.

Coaches and scouts skipped over Albany on their tours of Texas, so Wilson called Lubbock Christian coach Jimmy Shankle every week. He wanted to play middle infield. Shankle relented, let Wilson try out and brought him on. After two years in Lubbock, Wilson followed Shankle to Texas-San Antonio, and Cincinnati drafted him in the 33rd round. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=left border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Wilson raised pigs in his native West Texas.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

By that time, he was married to Prairie, and she accompanied him to Billings, Mont., for rookie ball two straight seasons, and Charleston, W.Va., where his career petered out. To keep Wilson in the organization, the Reds offered him a scouting job and later sent him to coach Adam Dunn, Austin Kearns and B.J. Ryan, among others, in Billings.

"In the wintertime, I'd go pheasant hunting, and I invited Brian along," says Ted Power, the former Reds pitcher and a coach with Wilson in Billings. "We hooked up with some old high school friends of mine, good ol' boys, farmers. Brian fit in like he'd known these guys for years. We were hunting in some really bad weather, snow and sleet. Any time a bird got up, it was hard to hit him. Brian missed four or five in a row. And then, when he missed another, one of my friends said, 'Now I can see why you went into coaching. You must've had a lousy average.' "

Wilson roared. If Prairie was the pragmatist, he was the romantic who welcomed change. So if his baseball career ended, his coaching career would start. And when that concluded, he'd move on to scouting.

"Brian was always the kind of person who jumped off the cliff and built his wings on the way down," Prairie says. "He didn't think of how he was going to do it. He didn't waste his time trying to figure it out. He just did it."

Like with his pigs. Wilson loved his pigs. He bought 80 acres in Albany and built his dream house, replete with a pig barn. His show pig, carefully bred, won first place in its class at a recent ag show in Houston. Once when Power called, Wilson was sitting on top of a 300-pound sow delivering babies. He kept talking anyway.

"He took his girls to the shows," says Johnny Almaraz, the Reds' farm director and Wilson's scouting mentor. "He kept asking me to bring my little girl along. So I did. And after the show, seeing what Brian did with the pigs, she said, 'I want pigs, too.' "

"Those girls," Wilt says, "thought he hung the moon. He loved baseball, but family is why he lived."

Family is probably also why he died.

Wilson's father had triple-bypass surgery at 40. His mother died in her early 50s after two strokes. Wilson went to a heart specialist in Houston following Vickie's death with a two-week chart of everything he ate and how much he exercised. Even though Wilson's diet and exercise plans were exceptional, his cholesterol remained high.

On June 17, a Saturday, Wilson, his brother-in-law Trent Tankersley and his youngest daughter, Curry, were lifting farrowing crates in which they would place their pregnant sows. Tankersley used a Bobcat to lift the crates, and Wilson was trying to slide a piece of piping to help roll them toward the back of the barn. He bent at the waist and collapsed. Tankersley rolled Wilson over. There was no pulse. His eyes were fixed. Tankersley thinks Wilson died before he hit the ground.

Nearly 1,000 people attended the funeral, family and friends, scouts and players. They asked why, aloud, and no one knew the answer.

"Somebody said after the funeral that Albany was going to need a new mayor," Wilt says. "Everywhere he went, Willy was mayor."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

He looked slick. At the Big 12 baseball tournament in 2002, Wilson showed up in Arlington, Texas, wearing shiny leather shoes, pressed slacks and a tailored dress shirt. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Wilson played three years and coached three years in the Reds' farm system before going into scouting.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

How he ended up squatting, with a pair of tennis shoes on his feet and a white T-shirt sheathing his torso, is part of what made Wilson a great scout.

Fearlessness is a scout's vital quality. To have inherent confidence in one's assessments and not worry about others' judgments separates the employed and unemployed, and Wilson, on that particular day, fully believed he could catch Scott Kazmir as he tried to learn a changeup.

Kazmir was no ordinary pitcher. He was a left-hander who threw 95, the Gala, Red Delicious and Granny Smith of every scout's eye. The Reds wondered if he could throw a change. When Kazmir, now an All-Star at 22 years old, volunteered to try, the group backed away like his arm was made of anthrax while Wilson stepped forward.

"So Willy changes – he's still wearing those dress pants – and gets down," Wilt says. "He doesn't have a cup, and here's a kid learning a pitch that sometimes bounces. You know what Willy was doing the whole time? Laughing."

No, Wilson wasn't an ordinary scout. He loved mining backwoods towns for players. When Prairie would ask where he was going, Wilson would answer: "To find the arm behind the barn."

Wilson started scouting in 1996, the year he retired, and would traverse Texas with Gonzales, from high schools to colleges to tryout camps, where he would test his heart by throwing eight or nine hours of batting practice. It always held up just fine.

He lagged in his organization. Instead of carrying a day planner, Wilson lugged around a huge desk calendar, taking each page, folding it until it fit in his back pocket, which bulged like a goiter. Consequently, his driving skills were fodder for teasing, too. With Wilson placing the calendar atop his dash board, talking on the phone and adjusting the radio, it's a wonder he wasn't the one who caused the morning accident.

Driving is a given in scouting life, though, so Wilson found ways to pass the time. He would blast '80s music, call Wilt and put the phone up to the speaker. If Wilt knew the band and the song, they would talk. If he didn't, Wilson hung up. Sometimes, even when Wilt got the answer right, Wilson hit the disconnect button anyway. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=left border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>[The girls] are where Brian is going to live on," Prairie Wilson says.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

"We would stay up late at night arguing about players," Wilt says, "and what I always took away from that was to have your opinion, stick to your guns, be passionate about what you believe and have some conviction to your thought process."

Everyone had those talks with Wilson. Because as much as Wilson enjoyed scouting, he hated that his schedule meant driving six hours, on deserted back roads, just so he could make it home to cook breakfast and take the girls to school.

"The job didn't help any," Gonzales says. "Stress is stress. And that was the most stressful time of the season. He had just signed Stubbs on Wednesday night. He was driving back home Thursday and was going to see another kid that day. I talked to him at 9 o'clock on Friday night. I was at a national showcase in Fayetteville. I said, 'I'll talk to you tomorrow.' I called him all day Saturday and couldn't get a hold of him."

Wilson was gone. Gonzales found out from Tankersley, and word spread quickly in the scouting community. Every time he dialed a number, Gonzalez numbed himself a little more. Scouting Texas without Wilson would be like watching black-and-white TV after years of seeing brilliant colors.

Gonzales used to called Wilson so much, Prairie joked they were the ones who actually were married.

"A few times," Gonzales says, "I've caught myself picking that phone up."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

Every day, Prairie Wilson reminds herself that she loves her husband as much as she did in fourth grade. Brian was a year ahead of her, and in between class, they would pass notes. He would write: "Do you like me? Circle yes or no." She saved the notes. She'll look at them when it's time.

For now, she's got two things: her memories and her daughters. She can think about two weeks ago, when she stepped outside and saw a rattlesnake. Wilson was on the road, so she called and asked how to kill it. Shoot it, he said. She took out his .410 shotgun and unloaded three blasts. Miss, miss, miss. Prarie fumed; Wilson calmed her.

"You still have one shell left," he said. "You can do it." <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Brian and Prairie started passing love notes in elementary school. They married when he was 20 and she was 19.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

He told her where to aim, and she split the snake in half.

"When I think of that story, I think of the girls, because they're where Brian is going to live on," Prairie says. "Our oldest has his quiet strength and ability to listen to people. Our second daughter has his fearlessness and his courage. And our youngest daughter has his free spirit, his love of life. Those are the things that carry me through. Looking at them and seeing him.

"He may not be here physically, but he's still here."

When Wilson returned from signing Stubbs, three days before he died, Prairie had tested out some paint for the downstairs of the new house, which they moved into Thanksgiving day. She brushed four potential colors on the wall.

"I really don't like it," Wilson said.

On Thursday, he came home after visiting a scouting friend's house. He had been looking for the right color and found one he liked. It was called Squirrel's Tail. The name made Prairie suspect.

"Today," she says, "I went to Abilene and bought Squirrel's Tail. That's fixing to be the color of our kitchen and living room." She opened the can and pulled a long brushstroke down the wall. Prairie thought of her husband, gone at 33, and looked at the color he chose, and she said, "It really is beautiful."

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

July 7, 2006

<TABLE id=ysparticleheadshot cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 align=left border=0 vspace="5" hspace="5"><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=3 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=2 width="100%" border=0><TBODY><TR><TD>

</TD></TR><TR><TD>

</TD></TR><TR><TD>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>The sound of twisting metal woke up the whole neighborhood. There had been a nasty accident. A 16-year-old fussing with the radio lost control of his car, crashed into a parked one and thrust it into the next driveway. The kid was OK, just nervous that the guy whose car he destroyed might kill him.

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>The sound of twisting metal woke up the whole neighborhood. There had been a nasty accident. A 16-year-old fussing with the radio lost control of his car, crashed into a parked one and thrust it into the next driveway. The kid was OK, just nervous that the guy whose car he destroyed might kill him. Brian Wilson, Cincinnati Reds scout, husband, father of three girls, pig farmer and, in this case, vehicle owner, emerged from the house. He was staying with Jimmy Gonzales, his good friend and also a Reds scout, and rather than survey the damage with narrowed and angry eyes, he walked to the car and emptied it.

"He knew it was totaled," Gonzales says. "So he got his stuff out of his car. His car was dirty, too. Things everywhere. In the back, he had a bunch of Reds hats. And with everybody outside, at 6:30 in the morning, he started passing out Reds hats. To the neighbors. To the cops. He gave one to the kid."

Scouts are the traveling salesmen of baseball, sentenced to lives on the road and overworked odometers. They are also the nurses, eminently underappreciated, and the teachers, terribly underpaid. And that is why when Brian Wilson, 33 years old, died of a heart attack on June 17, the news was relegated to a two-sentence blurb.

Paring Wilson's life down <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Back row: Brian Wilson and his wife, Prairie. Front row: daughters Conor, 10; Carson, 12; and Curry, 8.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>to a handful of words was like whittling a Sequoia into a walking stick. For the last 10 years, he worked his way up from area scout to supervisor for all of Texas. He signed the Reds' last two first-round picks, outfielders Jay Bruce and Drew Stubbs. He was Willy, parent-charmer and joke-teller, the walking compound adjective.

"He was the backbone of our scouting department," Gonzales says. "He wasn't just one of the veterans. He was the best evaluator, not even close, and he was as hard a worker, as far as production."

In Albany, Texas, the town of 1,900 where he grew up and lived, he was Brian. Whose daughters, Carson, 12, Conor, 10, and Curry, 8, let him clip and paint their toenails, because he was afraid their mom, Prairie, wouldn't do it right. Whose nose – protruding some might say, big and beautiful he'd contend – forced him to turn a soda can sideways if he wanted to drink it. Whose absent-mindedness seemed to lead his sunglasses astray, until someone pointed out they were resting atop his head, which would prompt him to say, "Hey, I'm just a redneck from West Texas."

For a redneck from West Texas, he gave good advice, and so friends and peers sought him out often to hear his simple wisdom. Two weeks before Wilson died, he got a call from Tyler Wilt, a scout with the Reds out of Chicago. He was Wilt's best friend, though a lot of people say that about Wilson. He helped Wilt ascend from a birddog in Texas to an integral part of the Reds' operations in the Midwest, and Wilt, suffering from a temporary bout with confidence, needed some reassurance.

"Don't let this job get to you," Wilson said. "If you have a heart attack and die, they'll just move on and give the job to someone else."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

One summer, Brian Wilson lived in the press box at Hays Field at Lubbock Christian College. It was 1991, and an injury forced him out of the summer Jayhawk League. He didn't want to go home to Albany, and the 750-seat stadium sat empty during the summer, so Wilson plopped a bed in the radio booth and hooked up a TV in the adjoining room.

"Cribs" it wasn't.

"But Brian was like Tom Sawyer painting the fence," Wilt says. "He made it sound so good. I was living in a four-bedroom house with my parents, and I was like, 'Boy, I wish I could live in a press box.' "

Born in Graham, Texas, Wilson moved an hour Southwest to Albany while in first grade. His mother, Vickie, was an English teacher, and his father, Carl, taught agriculture. And Wilson was the small-town jock incarnate: the football and baseball star who dated the captain of the cheerleading squad.

Coaches and scouts skipped over Albany on their tours of Texas, so Wilson called Lubbock Christian coach Jimmy Shankle every week. He wanted to play middle infield. Shankle relented, let Wilson try out and brought him on. After two years in Lubbock, Wilson followed Shankle to Texas-San Antonio, and Cincinnati drafted him in the 33rd round. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=left border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Wilson raised pigs in his native West Texas.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

By that time, he was married to Prairie, and she accompanied him to Billings, Mont., for rookie ball two straight seasons, and Charleston, W.Va., where his career petered out. To keep Wilson in the organization, the Reds offered him a scouting job and later sent him to coach Adam Dunn, Austin Kearns and B.J. Ryan, among others, in Billings.

"In the wintertime, I'd go pheasant hunting, and I invited Brian along," says Ted Power, the former Reds pitcher and a coach with Wilson in Billings. "We hooked up with some old high school friends of mine, good ol' boys, farmers. Brian fit in like he'd known these guys for years. We were hunting in some really bad weather, snow and sleet. Any time a bird got up, it was hard to hit him. Brian missed four or five in a row. And then, when he missed another, one of my friends said, 'Now I can see why you went into coaching. You must've had a lousy average.' "

Wilson roared. If Prairie was the pragmatist, he was the romantic who welcomed change. So if his baseball career ended, his coaching career would start. And when that concluded, he'd move on to scouting.

"Brian was always the kind of person who jumped off the cliff and built his wings on the way down," Prairie says. "He didn't think of how he was going to do it. He didn't waste his time trying to figure it out. He just did it."

Like with his pigs. Wilson loved his pigs. He bought 80 acres in Albany and built his dream house, replete with a pig barn. His show pig, carefully bred, won first place in its class at a recent ag show in Houston. Once when Power called, Wilson was sitting on top of a 300-pound sow delivering babies. He kept talking anyway.

"He took his girls to the shows," says Johnny Almaraz, the Reds' farm director and Wilson's scouting mentor. "He kept asking me to bring my little girl along. So I did. And after the show, seeing what Brian did with the pigs, she said, 'I want pigs, too.' "

"Those girls," Wilt says, "thought he hung the moon. He loved baseball, but family is why he lived."

Family is probably also why he died.

Wilson's father had triple-bypass surgery at 40. His mother died in her early 50s after two strokes. Wilson went to a heart specialist in Houston following Vickie's death with a two-week chart of everything he ate and how much he exercised. Even though Wilson's diet and exercise plans were exceptional, his cholesterol remained high.

On June 17, a Saturday, Wilson, his brother-in-law Trent Tankersley and his youngest daughter, Curry, were lifting farrowing crates in which they would place their pregnant sows. Tankersley used a Bobcat to lift the crates, and Wilson was trying to slide a piece of piping to help roll them toward the back of the barn. He bent at the waist and collapsed. Tankersley rolled Wilson over. There was no pulse. His eyes were fixed. Tankersley thinks Wilson died before he hit the ground.

Nearly 1,000 people attended the funeral, family and friends, scouts and players. They asked why, aloud, and no one knew the answer.

"Somebody said after the funeral that Albany was going to need a new mayor," Wilt says. "Everywhere he went, Willy was mayor."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

He looked slick. At the Big 12 baseball tournament in 2002, Wilson showed up in Arlington, Texas, wearing shiny leather shoes, pressed slacks and a tailored dress shirt. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Wilson played three years and coached three years in the Reds' farm system before going into scouting.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

How he ended up squatting, with a pair of tennis shoes on his feet and a white T-shirt sheathing his torso, is part of what made Wilson a great scout.

Fearlessness is a scout's vital quality. To have inherent confidence in one's assessments and not worry about others' judgments separates the employed and unemployed, and Wilson, on that particular day, fully believed he could catch Scott Kazmir as he tried to learn a changeup.

Kazmir was no ordinary pitcher. He was a left-hander who threw 95, the Gala, Red Delicious and Granny Smith of every scout's eye. The Reds wondered if he could throw a change. When Kazmir, now an All-Star at 22 years old, volunteered to try, the group backed away like his arm was made of anthrax while Wilson stepped forward.

"So Willy changes – he's still wearing those dress pants – and gets down," Wilt says. "He doesn't have a cup, and here's a kid learning a pitch that sometimes bounces. You know what Willy was doing the whole time? Laughing."

No, Wilson wasn't an ordinary scout. He loved mining backwoods towns for players. When Prairie would ask where he was going, Wilson would answer: "To find the arm behind the barn."

Wilson started scouting in 1996, the year he retired, and would traverse Texas with Gonzales, from high schools to colleges to tryout camps, where he would test his heart by throwing eight or nine hours of batting practice. It always held up just fine.

He lagged in his organization. Instead of carrying a day planner, Wilson lugged around a huge desk calendar, taking each page, folding it until it fit in his back pocket, which bulged like a goiter. Consequently, his driving skills were fodder for teasing, too. With Wilson placing the calendar atop his dash board, talking on the phone and adjusting the radio, it's a wonder he wasn't the one who caused the morning accident.

Driving is a given in scouting life, though, so Wilson found ways to pass the time. He would blast '80s music, call Wilt and put the phone up to the speaker. If Wilt knew the band and the song, they would talk. If he didn't, Wilson hung up. Sometimes, even when Wilt got the answer right, Wilson hit the disconnect button anyway. <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=left border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>[The girls] are where Brian is going to live on," Prairie Wilson says.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

"We would stay up late at night arguing about players," Wilt says, "and what I always took away from that was to have your opinion, stick to your guns, be passionate about what you believe and have some conviction to your thought process."

Everyone had those talks with Wilson. Because as much as Wilson enjoyed scouting, he hated that his schedule meant driving six hours, on deserted back roads, just so he could make it home to cook breakfast and take the girls to school.

"The job didn't help any," Gonzales says. "Stress is stress. And that was the most stressful time of the season. He had just signed Stubbs on Wednesday night. He was driving back home Thursday and was going to see another kid that day. I talked to him at 9 o'clock on Friday night. I was at a national showcase in Fayetteville. I said, 'I'll talk to you tomorrow.' I called him all day Saturday and couldn't get a hold of him."

Wilson was gone. Gonzales found out from Tankersley, and word spread quickly in the scouting community. Every time he dialed a number, Gonzalez numbed himself a little more. Scouting Texas without Wilson would be like watching black-and-white TV after years of seeing brilliant colors.

Gonzales used to called Wilson so much, Prairie joked they were the ones who actually were married.

"A few times," Gonzales says, "I've caught myself picking that phone up."

<HR align=center width="20%" SIZE=1>

Every day, Prairie Wilson reminds herself that she loves her husband as much as she did in fourth grade. Brian was a year ahead of her, and in between class, they would pass notes. He would write: "Do you like me? Circle yes or no." She saved the notes. She'll look at them when it's time.

For now, she's got two things: her memories and her daughters. She can think about two weeks ago, when she stepped outside and saw a rattlesnake. Wilson was on the road, so she called and asked how to kill it. Shoot it, he said. She took out his .410 shotgun and unloaded three blasts. Miss, miss, miss. Prarie fumed; Wilson calmed her.

"You still have one shell left," he said. "You can do it." <TABLE style="PADDING-RIGHT: 5px; PADDING-LEFT: 5px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 5px; PADDING-TOP: 5px" cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=0 align=right border=0><TBODY><TR><TD><TABLE cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=1 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD class=ysptblbdr2><TABLE class=yspwhitebg cellSpacing=0 cellPadding=5 width=310 border=0><TBODY><TR><TD align=middle>

<SMALL>Brian and Prairie started passing love notes in elementary school. They married when he was 20 and she was 19.</SMALL>

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE></TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>

He told her where to aim, and she split the snake in half.

"When I think of that story, I think of the girls, because they're where Brian is going to live on," Prairie says. "Our oldest has his quiet strength and ability to listen to people. Our second daughter has his fearlessness and his courage. And our youngest daughter has his free spirit, his love of life. Those are the things that carry me through. Looking at them and seeing him.

"He may not be here physically, but he's still here."

When Wilson returned from signing Stubbs, three days before he died, Prairie had tested out some paint for the downstairs of the new house, which they moved into Thanksgiving day. She brushed four potential colors on the wall.

"I really don't like it," Wilson said.

On Thursday, he came home after visiting a scouting friend's house. He had been looking for the right color and found one he liked. It was called Squirrel's Tail. The name made Prairie suspect.

"Today," she says, "I went to Abilene and bought Squirrel's Tail. That's fixing to be the color of our kitchen and living room." She opened the can and pulled a long brushstroke down the wall. Prairie thought of her husband, gone at 33, and looked at the color he chose, and she said, "It really is beautiful."

</TD></TR></TBODY></TABLE>