From a Benz to a bike<!-- begin pres by --> <!-- end pres by -->

By Jeff Pearlman

By Jeff Pearlman

Special to Page 2

(Archive | Contact)

<!-- promo plug -->

<!-- end promo plug -->

<!-- end story header --><!-- begin left column --> <!-- begin page tools --> Updated: January 10, 2008, 1:48 PM ET

<!-- end page tools --><!-- begin story body --> <!-- template inline -->Lord, where my life go?

Lord, it's real.

The pain I feel.

As I struggle up this long hill.

Life's so strange.

It's filled with these pressures and pains.

That make you veer away from your game.

Now you've lost your aim.

And it's all a part of the game.

To see if you can rise and maintain.

There's so many things to blame.

Yes, there's a blame.

-- Lyrics from Clayton Holmes' song "Lord, Where My Life Go?"

FLORENCE, S.C. -- His bicycle, naturally, is red. Not brown or black or forest green or any of the 2,000 other hues that generally fail to catch the eyes of passers-by.

It is red.

Somehow, in the drearily colored life of Clayton Holmes, this makes perfect sense. Were his bike, say, gray, Holmes would more easily slip into the backdrop of the east side of Florence, a downtrodden section of a downtrodden city littered by double-wide trailers, wayward drug dealers and the shattered Budweiser bottles, used condoms, McDonald's wrappers and crumpled newspapers that seem to pock each dirt road and cement walkway. Although as a boy Holmes was raised in a trailer at 1018 West Harmony St., the only harmonious element to Florence's poor neighborhoods is the occasional crooning from drunk and cracked-up men on particularly jovial nights.

"Florence," says Clinton Holmes, Clayton's younger brother, "can bring any person down. We're talking about a very, very negative place."

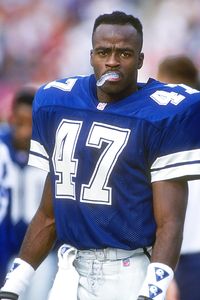

[+] Enlarge

Jonathan Hayt/WireImage.com

Jonathan Hayt/WireImage.com

Clayton Holmes was on top of the world as a member of the Dallas Cowboys in the early 1990s.

It is through this bottomed-out world that Clayton Holmes, 38-year-old Florence native, weaves his red bicycle on a daily basis. Maybe he'll ride down Christopher Lane, make a left on Prout Drive and a right on Church Street. Or perhaps he'll visit his uncle Timothy, pastor of the Faith Kingdom Builders Church one mile away on Brogdon Street. Really, the path he follows matters not when it comes to the ensuing travesty:Wherever Holmes rides, he is ruthlessly mocked.

In a city long ago deserted by hope, Holmes was the one who got out, who grabbed the golden ring and extracted himself from the neck-high sludge. Following an All-America career at Carson-Newman College, he was selected by the Dallas Cowboys in the third round of the 1992 NFL draft. Over the next four years, Holmes went on to win three Super Bowl rings as a defensive back and special teams wiz.

Boasting 4.23 speed and Carl Lewis-esque athleticism, he was the type of out-of-nowhere phenom that Jerry Jones and Jimmy Johnson prided themselves on. "Clayton was such a damn talent," says Darren Woodson, a former Cowboys safety who was selected in the same draft as Holmes. "As far as the guys I played with in my 13-year career, I'd put him in my top four as far as pure athletic ability. He could do anything. Everything."

And now, here is Holmes, back on the very streets he once escaped, trying to lie low atop a red bicycle that serves, unintentionally, as his calling card. More than 12 years removed from his last regular-season NFL game, Holmes is well versed in the inescapable hell that is the pity and scorn directed his way. He hears people whispering, sees them pointing, understands the joke is completely on him. When the football money rolled in, Holmes was quick to send $500 here, $1,000 there.

Clayton, my car is broken. Clayton, my son needs new shoes. Clayton, my house payment is overdue.

"He couldn't say no," says Lisa Holmes, Clayton's ex-wife. "He felt like he had to help everyone."

Now, those same people he aided look at Holmes as a cautionary tale: what not to do.

They consider it their right -- their obligation -- to tell him what a pathetic fool he is; to tell him that he had The Life and lost it; to tell him that he should be on TV with Deion and Emmitt and Troy and Moose, not slogging around Florence like a worthless bum.

You don't even have a car. You don't even have a cell phone. You don't even have a home. You pawned your Super Bowl rings. You have four kids with four women.

"Clayton has turned out to be a great disappointment," says Claudia McElveen, Holmes' mother. "There's no other way to say it."

If Holmes' bicycle is emblematic of tough times, his living conditions serve as a neon billboard. The man who once owned a $250,000 Dallas home and drove a white Mercedes 560 SEC ("I went from a Benz to a bike," he glumly notes) now dwells in a decrepit shack in the front yard of his mother's trailer. It lacks both running water and electricity; the lone source of power is an orange extension cord that snakes its way from an outlet beside Claudia's door, through the yard, to a light above Holmes' bed. Here, amidst the tattered carpet and peeling paint and empty cereal and microwavable popcorn boxes, a man once gifted with everything ponders how an affinity for marijuana and cocaine prematurely destroyed his football career; how a suicide attempt nearly ended his existence; how his four children barely know their father; how the dreams of yesteryear have shriveled up and died; how he wishes he could step on the pedals of his red bicycle and roll off into a different town. A different world. A different … life.

[+] Enlarge

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Holmes' current home is a far cry from the lifestyle he enjoyed while playing in the NFL.

"It's hard being the f---up," he says. "I'm not just saying that. Everyone here sees me as the f---up, as the guy who made it to the NFL and made a huge mistake. I'm the f---up to my mom, I'm the f---up to my dad, I'm the f---up to my family …"Holmes pauses. He is sitting at a table inside an off-the-path dive named Orange Land Seafood, jabbing a plastic fork into a slab of overcooked whiting. In the background, Otis Redding's "Try a Little Tenderness" hums from a speaker.

Come on and try

Try a little tenderness

Yeah try

Just

keep on trying

Holmes takes a bite, taps his hand along with the beat.

"Tenderness," he says. "That sounds awfully nice to me."

<hr align="left" width="150">I initially met Clayton Holmes eight months ago, when I flew to Florence to interview him for a book on the 1990s Dallas Cowboys. At the time, what I knew of the man was rather basic: Held the South Carolina state long jump record. Attended Carson-Newman. Spent four seasons as a reserve defensive back with America's Team. Was signed and released by the Miami Dolphins within a span of six months. Five drug suspensions. Liked the strippers. Vanished.

What I discovered in person, however, was anything but the typical ex-athlete. Holmes was modest, polite, soft-spoken and reflective. He dismissed his past athletic achievements as relatively meaningless but joyfully recalled his days alongside Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Michael Irvin in the Cowboys' locker room, when teammates affectionately called him "Chip Head" for his Kid 'n Play haircut. Holmes possesses an elephantine memory, easily pulling out the details of games and names and dates as if they were from last week, not 15 years ago. "I looked into coach Johnson's eyes," he said of one matchup against the Washington Redskins, "and knew we were gonna win …"

Yet, behind the funny stories and fourth-and-7 recollections, there was something … deeper. After spending the first two hours of our time together speaking of all things America's Team, Holmes gazed at me from across the table and said, simply, "I need to help people."

"Help people?" I asked.

"Yeah," he said. "Help people to not end up like me."

With that, Holmes launched into a 1½-hour mea culpa on a life gone bad; on misdeeds and mistakes; on late-night parties and long-legged women; on money earned and money squandered. Mostly, on how the wrong upbringing can crush the human spirit.

"I want to show people that it doesn't have to be this way," he said.

"People tend to look at one person who's made multiple mistakes and think, 'What a f---up! What's wrong with that guy?' But that's a simplistic view of a complicated problem. It's rarely just one person messing up. It's a pattern -- a long, long pattern of parental abuse and ignorance and negativity. Horrible negativity.

"People who say, 'What's wrong with Clayton Holmes?' are missing the bigger picture. Yeah, I've screwed up -- more times than I can count. But until we stop these patterns, it's an ongoing problem. That's why I want to tell my story. To let folks know. To help put an end to people winding up like me.

"I need to be heard."

<hr align="left" width="150">Clayton Holmes was born Aug. 23, 1969, at Florence's McLeod Medical Center to a man, Phillip Windom, and a woman, Claudia Holmes, who knew little of raising children with love and compassion, but grasped all too well that life -- from rise to shut-eye -- was one ceaseless struggle.

The couple met in the late 1960s, when Phillip went to Richmond, Va., to help Claudia's mother move. At the time, Claudia was in her early 20s, with a world's worth of scars. She first married at age 16, and her husband Calvin was fatally shot while shopping at a nearby store.

Then, less than a year later, her brother, Harry Jr., was killed while serving in Vietnam. "I couldn't handle any of it," Claudia says. "I was young and heartbroken, working as a singer in a Richmond club and smoking weed and drinking and having sex. I was buck wild, hurting from a lot of pain."

Her relationship with Phillip was, to delve into severe understatement, love-hate. One day, he was the world's greatest man. The next day, Claudia was unloading the bullets from a .22 caliber into his body. Although the two never wed, they dated for five years. "This particular night, I was working at a bar and a man touched my hand," she says. "Well, Phillip was very jealous. He grabbed me by the hair, pulled me over the bar and carried me out. When he backed up, I pulled my gun out of my pocketbook and shot him. Bam! Shot him good."

By the time Clayton was born, Claudia had shot Phillip a second time (he survived; their relationship didn't) and had given birth to two other sons by two men. Although Phillip materialized every so often to present Clayton with sneakers, a T-shirt or a day trip to a sandlot baseball game, the boy was raised solely by Claudia, who -- according to Clayton -- was physically, verbally and emotionally abusive. From his earliest memories, Clayton recalls his mother's mocking him as "stupid" and "worthless." When he asked for help with homework, she dismissed him with a quick, "What, are you dumb?" He watched in fear as she beat his older brothers, Bam and Curtis, with bats and brooms. "She didn't quite go the wood route with me," Clayton says. "The worst thing she ever hit me with was an extension cord."

Coupled with a strangling poverty that had Clayton and his three brothers (Clinton, the youngest, was born four years after Clayton) sharing underwear, pants, shirts and beds, the future football star walked through the hallways of Carver Elementary and Williams Junior High with his chin glued to his chest and his eyes toward the floor -- "a kid in torn jeans with snot dripping from his nose," he says. In one particularly painful episode that still causes Holmes to grimace, a handful of girls stopped him in the Carver hallway, pulled down his pants and mocked the size of his penis. "Talk about a scarring moment," he says. "That was just …"

His voice trails off. One can see the anguish etched on Holmes' face. Yet nothing -- absolutely nothing -- wounded Clayton as deeply as those nights when Bam, seven years his elder, sneaked into bed, saddled up from behind, placed a hand over his mouth and molested him. And although young Clayton feared his eldest brother (Bam spent his life in and out of jail on robbery and drug convictions), he also emulated him. When Bam stole, Clayton stole. When Bam talked trash, Clayton talked trash. "I loved him and despised him," he says. "But when he would touch me … it changed who I was … what I felt. It brought a lot of anger out of me. Look, I was a kid who was supposed to be having fun, going to school, playing sports. Instead, I had a mother who beat me and a brother who molested me." When, 11 years ago, Bam died of AIDS-related causes, Clayton attended the funeral and seethed. "You're not supposed to hate someone who passed," he says. "I loved Bam, but I hated him."

[+] Enlarge

Otto Greule Jr. /Getty Images

Otto Greule Jr. /Getty Images

Holmes' abilities brought him acclaim at Carson-Newman and allowed him to become a third-round pick by the Cowboys in 1992.

By the time Clayton turned 13, Phillip -- concerned by one too many tales of neglect -- sued Claudia for custody of his son. A railroad maintenance operator who spent Sundays through Thursdays on the road, Phillip, like Claudia, believed in ruthless discipline. Only, he was significantly stronger than Claudia. "One time I broke into a house, and my dad caught me," Clayton says. "He said to me, 'Clayton, tell me why you did it -- and you better not say you don't know why and you better not cry.'"Clayton started to sob.

POP!

"He punched me in the face with his fist," Clayton says. "Knocked me out cold. But I don't believe he and my mom were intentionally trying to ruin me. It was how they knew to parent … what they were taught by their parents."

If there is a bright side to anger -- to pure, unadulterated anger -- it is that it can be recharged and routed elsewhere. Holmes took the beatings and the mocking and the molestation, and used it to become one of the best athletes in Wilson High School history. He starred as a wishbone quarterback in football, a fleet-footed center fielder in baseball, the school's No. 4 tennis player and one of the two or three best long jumpers South Carolina has ever seen. Because of low test scores and grades in the C-minus range, after Holmes graduated in 1988, he enrolled at North Greenville Junior College, where he led the first-year football program to a 9-1 mark. "He was the best athlete in South Carolina," says Mike Taylor, the North Greenville coach.

"I'll never forget Clayton's explosiveness. It was unparalleled."

Although he has been coaching for 30 years, Taylor still raves over a play from Holmes' sophomore season, when he ran for a 60-yard quarterback sneak with an Aircast guarding a fractured left ankle.

"You gave Clayton the ball," Taylor says, "you knew a touchdown was coming."

While his myriad athletic abilities brought to mind Deion Sanders, Holmes was modest and soft-spoken. He rarely drank, never smoked cigarettes or marijuana, and, recalls his ex-wife, "wouldn't even take a Tylenol."

"Clayton was wonderful," says Lisa, who met Holmes while studying at Carson-Newman, a liberal arts school in Jefferson City, Tenn. "He was very mannerly, very humble. I remember the summer before we started dating, he was at school by himself with no money, no transportation and an empty refrigerator. We're talking about someone who could have starved to death -- but he always saw the bright side."

In two seasons at Carson-Newman, Holmes emerged as the nation's top NAIA cornerback, winning the South Atlantic Conference's Defensive Player of the Year award and earning buzz as a potential sleeper in the '92 draft. On the afternoon of April 26, Holmes sat in his bedroom as family and friends swarmed around the television, anxious to learn who would transform him from broke collegiate nobody to wealthy NFL somebody. When the phone rang, a nervous Clayton picked up.

"Hello?" he said.

"Clayton?"

"Yes."

"This is Jerry Jones from the Dallas Cowboys. How do you feel about wearing a star on your helmet?"

<hr align="left" width="150">It all happened too fast. Holmes can see that now, far removed from the action-packed days and dizzying nights of Dallas. But at the time, in the midst of it all, everything just seemed so … so … right. Dallas Cowboys bought fancy cars, so Clayton Holmes bought fancy cars. Dallas Cowboys bought big houses, so Clayton Holmes bought a big house. Dallas Cowboys flipped $100 bills to exotic dancers, so Clayton Holmes flipped $100 bills to exotic dancers. Following a rookie year during which he tied for second on the club with 15 special teams tackles and had a fumble recovery in the Super Bowl triumph over the Buffalo Bills, Clayton proposed to Lisa, his girlfriend of two years, because, well, that's what he was supposed to do. "I was an adult," he says. "Adults get married."

Only, Holmes wasn't an adult. Oh, his driver's license listed him as 23 years old. But, really, what did he know about being a professional football player? About being a man? About being a husband? One day, you're being molested by your brother in the Florence projects. The next, you're a big-time football player being asked to sign a contract worth more than your family's entire life earnings. "How," Holmes asks, "can that possibly work?" The kid who grew up believing that children were made to be beaten and wives were made to be cheated on and money needed to be spent ASAP was one of hundreds of athletes who have entered professional sports with absolutely no concept of how to live a righteous life. Heck, Holmes had never opened a bank account or written a check. "When I signed my first contract, I was thinking, 'I'm a millionaire! I'm set for life!'" he says of the two-year, $1.3 million deal (featuring a $200,000 signing bonus). A short laugh. "That's how naive I was."

[+] Enlarge

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Once again living in his hometown of Florence, S.C., Holmes hopes others can learn from his story.

Long-lost friends and relatives materialized from thin air, smiles wide, palms extended. Although Claudia had largely retreated from her son's life, attending only one of his high school games and none of his collegiate football games, suddenly she was back in the picture. "When Clayton made the NFL, he was her baby again," Phillip says. "I tried to warn him, but he didn't listen." (Says Claudia: "I didn't go to his games because I hated watching him get hit.") Clayton supplied his mother with money, paid off her debts, purchased a new home for her to live in and a car for her to drive. "She wanted a lot," Clayton says, "and was never afraid to ask." (Counters Claudia: "He didn't buy me a house. If he had bought me a house, my name would have been on the paperwork. Yes, I lived in it. But it belonged to Clayton. And the car he bought me only cost $3,000 and was from 1986. Big deal.")On Jan. 9, 1993, Lisa gave birth to the couple's first child, a daughter named Briana. Holmes' initial reaction was, "Run!" He already had a 6-year-old son, Dominique, from a high school girlfriend -- and now this? It was too much. Too real.

Then, the beginning of the end came on Aug. 14, 1993, when Holmes tore ligaments in his right knee during an exhibition game against the Oakland Raiders and learned he would miss the season. Bored and lonely without the sport he loved, he started drinking heavily, smoking pot, cheating on his wife and disappearing for one- and two-day stretches.

When he wasn't home, Holmes often could be found at the strip clubs, hypnotized by the dancers and blowing large wads of money. When, in 1995, he was suspended for one year for testing positive for cocaine, few were surprised. "I never thought of myself as an addict … never felt like I had to have it," he says. "But the drugs relaxed me. I wasn't a person who was comfortable making conversation. But when I was high, people listened to me. The words flowed from my mouth, and I made sense."

In 1995, Lisa took Briana and returned to her hometown of Knoxville, Tenn., leaving Holmes alone with his demons in Dallas. He didn't last long.

Holmes appeared in eight games with the '95 Cowboys, but his drug problems and inconsistent play made him easy to relinquish. Suspended for the entire 1996 season, Holmes signed with the Dolphins in March 1997, after Miami coach Jimmy Johnson called his former player and asked if he was clean.

Holmes said he was.

Holmes wasn't.

That August, he flunked yet another drug test, prompting the Dolphins to release him ("I'm concerned for his future," Johnson told the Tampa Tribune) into the real world. Over the ensuing years, Holmes fathered children with two strippers, underwent substance-abuse and psychological counseling, took a job as a supervisor at the Forbes Juvenile Detention Center in Topeka, Kan., played a season for the Topeka Knights of the Indoor Football League (salary: $200 per game) and, in 1998, moved to Knoxville to be closer to his daughter and ex-wife. It was while living in the Marble City that Holmes plummeted to a new low. His career long dead, his money long gone, his résumé nonexistent (he is 17 credits shy of graduating from college), Clayton was working a low-wage security job. "That's when his mother came to Knoxville and told Clayton she was behind on the mortgage on his house and needed him to pay," Lisa says. "For her to tell him that, well, it was a knife to his heart."

The following afternoon, Holmes swallowed eight Trazodones and closed his eyes. "I wanted to call it quits," he says. "But as I started dozing off, I decided I couldn't go through with it. I guess there was too much to live for." Holmes dialed 911, passed out and woke up the following morning in Peninsula Hospital, a tube stuck down his throat.

<hr align="left" width="150">Three years ago, following mounds of therapy sessions and years of self-reflection, Clayton Holmes decided he needed to return to the place where -- the way he sees it -- Frankenstein's monster was constructed.

He needed to return to Florence.

It has not been pretty.

At first, Holmes' mother and father seemed to support his desire for space and quiet. They kept their distance, letting him sleep when he wanted to sleep, eat when he wanted to eat, talk when he wanted to talk. Now, they are exasperated. "He needs to find a purpose," Phillip says. "Something meaningful." Holmes held a bevy of personal training jobs in the area, but -- like the Super Bowl rings he pawned off -- failed to keep them. He now trains five clients per week at the local high school, charging $25 an hour.

At his best, Holmes is kind, charming and well-intentioned. When the 12-year-old son of a cousin recently admired two of his old NFL jerseys, Holmes whipped the garments out of a cardboard box and handed them over. "They were his last two jerseys," says Travis Hunter, the cousin. "He insisted, 'Take them, take them, take them.' People say, 'So-and-so would give you the shirt off his back,' and it's always a cliche. But Clayton will literally give you everything you need."

Yet, Holmes remains an enigma. When he is not riding his bicycle, he spends most of his days holed up in his hovel, jotting thoughts into a spiral notepad, or writing songs and recording them into a microcassette recorder, or planning a potential move to Washington, D.C., where he wants to immerse himself in Scientology. Although he owes more than $2,500 per month in child support, he is unmoved to find work at, say, the local Holiday Inn or Burger King.

"Here's the truth," he says. "Most fathers would be like, 'I have to take care of my kids, and it doesn't matter how I go about that.' I don't have that drive. I'm just being honest -- it's not there for me. I feel a connection with my kids but not an urgency."

Holmes takes a deep breath. He is wrong, and he knows it.

"I have not been a good father to my children. I was a lousy husband.

"But that's why I want to be heard. I'm part of a long line of people who think and act just like I do. The people who raised me tried to do right, but they knew no better. It needs to stop. It has to stop.

"Parents have to love and cherish and look out for their kids, or else they're gonna wind up just like me."

Another pause.

"Like me," he says. "Lost."

Jeff Pearlman is a former Sports Illustrated senior writer and the author of "Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero," now available in paperback. You can reach him at anngold22@gmail.com.

By Jeff Pearlman

By Jeff PearlmanSpecial to Page 2

(Archive | Contact)

<!-- promo plug -->

<!-- end promo plug -->

<!-- end story header --><!-- begin left column --> <!-- begin page tools --> Updated: January 10, 2008, 1:48 PM ET

<!-- end page tools --><!-- begin story body --> <!-- template inline -->Lord, where my life go?

Lord, it's real.

The pain I feel.

As I struggle up this long hill.

Life's so strange.

It's filled with these pressures and pains.

That make you veer away from your game.

Now you've lost your aim.

And it's all a part of the game.

To see if you can rise and maintain.

There's so many things to blame.

Yes, there's a blame.

-- Lyrics from Clayton Holmes' song "Lord, Where My Life Go?"

FLORENCE, S.C. -- His bicycle, naturally, is red. Not brown or black or forest green or any of the 2,000 other hues that generally fail to catch the eyes of passers-by.

It is red.

Somehow, in the drearily colored life of Clayton Holmes, this makes perfect sense. Were his bike, say, gray, Holmes would more easily slip into the backdrop of the east side of Florence, a downtrodden section of a downtrodden city littered by double-wide trailers, wayward drug dealers and the shattered Budweiser bottles, used condoms, McDonald's wrappers and crumpled newspapers that seem to pock each dirt road and cement walkway. Although as a boy Holmes was raised in a trailer at 1018 West Harmony St., the only harmonious element to Florence's poor neighborhoods is the occasional crooning from drunk and cracked-up men on particularly jovial nights.

"Florence," says Clinton Holmes, Clayton's younger brother, "can bring any person down. We're talking about a very, very negative place."

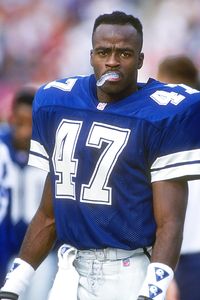

[+] Enlarge

Jonathan Hayt/WireImage.com

Jonathan Hayt/WireImage.comClayton Holmes was on top of the world as a member of the Dallas Cowboys in the early 1990s.

It is through this bottomed-out world that Clayton Holmes, 38-year-old Florence native, weaves his red bicycle on a daily basis. Maybe he'll ride down Christopher Lane, make a left on Prout Drive and a right on Church Street. Or perhaps he'll visit his uncle Timothy, pastor of the Faith Kingdom Builders Church one mile away on Brogdon Street. Really, the path he follows matters not when it comes to the ensuing travesty:Wherever Holmes rides, he is ruthlessly mocked.

In a city long ago deserted by hope, Holmes was the one who got out, who grabbed the golden ring and extracted himself from the neck-high sludge. Following an All-America career at Carson-Newman College, he was selected by the Dallas Cowboys in the third round of the 1992 NFL draft. Over the next four years, Holmes went on to win three Super Bowl rings as a defensive back and special teams wiz.

Boasting 4.23 speed and Carl Lewis-esque athleticism, he was the type of out-of-nowhere phenom that Jerry Jones and Jimmy Johnson prided themselves on. "Clayton was such a damn talent," says Darren Woodson, a former Cowboys safety who was selected in the same draft as Holmes. "As far as the guys I played with in my 13-year career, I'd put him in my top four as far as pure athletic ability. He could do anything. Everything."

And now, here is Holmes, back on the very streets he once escaped, trying to lie low atop a red bicycle that serves, unintentionally, as his calling card. More than 12 years removed from his last regular-season NFL game, Holmes is well versed in the inescapable hell that is the pity and scorn directed his way. He hears people whispering, sees them pointing, understands the joke is completely on him. When the football money rolled in, Holmes was quick to send $500 here, $1,000 there.

Clayton, my car is broken. Clayton, my son needs new shoes. Clayton, my house payment is overdue.

"He couldn't say no," says Lisa Holmes, Clayton's ex-wife. "He felt like he had to help everyone."

Now, those same people he aided look at Holmes as a cautionary tale: what not to do.

They consider it their right -- their obligation -- to tell him what a pathetic fool he is; to tell him that he had The Life and lost it; to tell him that he should be on TV with Deion and Emmitt and Troy and Moose, not slogging around Florence like a worthless bum.

You don't even have a car. You don't even have a cell phone. You don't even have a home. You pawned your Super Bowl rings. You have four kids with four women.

"Clayton has turned out to be a great disappointment," says Claudia McElveen, Holmes' mother. "There's no other way to say it."

If Holmes' bicycle is emblematic of tough times, his living conditions serve as a neon billboard. The man who once owned a $250,000 Dallas home and drove a white Mercedes 560 SEC ("I went from a Benz to a bike," he glumly notes) now dwells in a decrepit shack in the front yard of his mother's trailer. It lacks both running water and electricity; the lone source of power is an orange extension cord that snakes its way from an outlet beside Claudia's door, through the yard, to a light above Holmes' bed. Here, amidst the tattered carpet and peeling paint and empty cereal and microwavable popcorn boxes, a man once gifted with everything ponders how an affinity for marijuana and cocaine prematurely destroyed his football career; how a suicide attempt nearly ended his existence; how his four children barely know their father; how the dreams of yesteryear have shriveled up and died; how he wishes he could step on the pedals of his red bicycle and roll off into a different town. A different world. A different … life.

[+] Enlarge

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.comHolmes' current home is a far cry from the lifestyle he enjoyed while playing in the NFL.

"It's hard being the f---up," he says. "I'm not just saying that. Everyone here sees me as the f---up, as the guy who made it to the NFL and made a huge mistake. I'm the f---up to my mom, I'm the f---up to my dad, I'm the f---up to my family …"Holmes pauses. He is sitting at a table inside an off-the-path dive named Orange Land Seafood, jabbing a plastic fork into a slab of overcooked whiting. In the background, Otis Redding's "Try a Little Tenderness" hums from a speaker.

Come on and try

Try a little tenderness

Yeah try

Just

keep on trying

Holmes takes a bite, taps his hand along with the beat.

"Tenderness," he says. "That sounds awfully nice to me."

<hr align="left" width="150">I initially met Clayton Holmes eight months ago, when I flew to Florence to interview him for a book on the 1990s Dallas Cowboys. At the time, what I knew of the man was rather basic: Held the South Carolina state long jump record. Attended Carson-Newman. Spent four seasons as a reserve defensive back with America's Team. Was signed and released by the Miami Dolphins within a span of six months. Five drug suspensions. Liked the strippers. Vanished.

What I discovered in person, however, was anything but the typical ex-athlete. Holmes was modest, polite, soft-spoken and reflective. He dismissed his past athletic achievements as relatively meaningless but joyfully recalled his days alongside Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Michael Irvin in the Cowboys' locker room, when teammates affectionately called him "Chip Head" for his Kid 'n Play haircut. Holmes possesses an elephantine memory, easily pulling out the details of games and names and dates as if they were from last week, not 15 years ago. "I looked into coach Johnson's eyes," he said of one matchup against the Washington Redskins, "and knew we were gonna win …"

Yet, behind the funny stories and fourth-and-7 recollections, there was something … deeper. After spending the first two hours of our time together speaking of all things America's Team, Holmes gazed at me from across the table and said, simply, "I need to help people."

"Help people?" I asked.

"Yeah," he said. "Help people to not end up like me."

With that, Holmes launched into a 1½-hour mea culpa on a life gone bad; on misdeeds and mistakes; on late-night parties and long-legged women; on money earned and money squandered. Mostly, on how the wrong upbringing can crush the human spirit.

"I want to show people that it doesn't have to be this way," he said.

"People tend to look at one person who's made multiple mistakes and think, 'What a f---up! What's wrong with that guy?' But that's a simplistic view of a complicated problem. It's rarely just one person messing up. It's a pattern -- a long, long pattern of parental abuse and ignorance and negativity. Horrible negativity.

"People who say, 'What's wrong with Clayton Holmes?' are missing the bigger picture. Yeah, I've screwed up -- more times than I can count. But until we stop these patterns, it's an ongoing problem. That's why I want to tell my story. To let folks know. To help put an end to people winding up like me.

"I need to be heard."

<hr align="left" width="150">Clayton Holmes was born Aug. 23, 1969, at Florence's McLeod Medical Center to a man, Phillip Windom, and a woman, Claudia Holmes, who knew little of raising children with love and compassion, but grasped all too well that life -- from rise to shut-eye -- was one ceaseless struggle.

The couple met in the late 1960s, when Phillip went to Richmond, Va., to help Claudia's mother move. At the time, Claudia was in her early 20s, with a world's worth of scars. She first married at age 16, and her husband Calvin was fatally shot while shopping at a nearby store.

Then, less than a year later, her brother, Harry Jr., was killed while serving in Vietnam. "I couldn't handle any of it," Claudia says. "I was young and heartbroken, working as a singer in a Richmond club and smoking weed and drinking and having sex. I was buck wild, hurting from a lot of pain."

Her relationship with Phillip was, to delve into severe understatement, love-hate. One day, he was the world's greatest man. The next day, Claudia was unloading the bullets from a .22 caliber into his body. Although the two never wed, they dated for five years. "This particular night, I was working at a bar and a man touched my hand," she says. "Well, Phillip was very jealous. He grabbed me by the hair, pulled me over the bar and carried me out. When he backed up, I pulled my gun out of my pocketbook and shot him. Bam! Shot him good."

By the time Clayton was born, Claudia had shot Phillip a second time (he survived; their relationship didn't) and had given birth to two other sons by two men. Although Phillip materialized every so often to present Clayton with sneakers, a T-shirt or a day trip to a sandlot baseball game, the boy was raised solely by Claudia, who -- according to Clayton -- was physically, verbally and emotionally abusive. From his earliest memories, Clayton recalls his mother's mocking him as "stupid" and "worthless." When he asked for help with homework, she dismissed him with a quick, "What, are you dumb?" He watched in fear as she beat his older brothers, Bam and Curtis, with bats and brooms. "She didn't quite go the wood route with me," Clayton says. "The worst thing she ever hit me with was an extension cord."

Coupled with a strangling poverty that had Clayton and his three brothers (Clinton, the youngest, was born four years after Clayton) sharing underwear, pants, shirts and beds, the future football star walked through the hallways of Carver Elementary and Williams Junior High with his chin glued to his chest and his eyes toward the floor -- "a kid in torn jeans with snot dripping from his nose," he says. In one particularly painful episode that still causes Holmes to grimace, a handful of girls stopped him in the Carver hallway, pulled down his pants and mocked the size of his penis. "Talk about a scarring moment," he says. "That was just …"

His voice trails off. One can see the anguish etched on Holmes' face. Yet nothing -- absolutely nothing -- wounded Clayton as deeply as those nights when Bam, seven years his elder, sneaked into bed, saddled up from behind, placed a hand over his mouth and molested him. And although young Clayton feared his eldest brother (Bam spent his life in and out of jail on robbery and drug convictions), he also emulated him. When Bam stole, Clayton stole. When Bam talked trash, Clayton talked trash. "I loved him and despised him," he says. "But when he would touch me … it changed who I was … what I felt. It brought a lot of anger out of me. Look, I was a kid who was supposed to be having fun, going to school, playing sports. Instead, I had a mother who beat me and a brother who molested me." When, 11 years ago, Bam died of AIDS-related causes, Clayton attended the funeral and seethed. "You're not supposed to hate someone who passed," he says. "I loved Bam, but I hated him."

[+] Enlarge

Otto Greule Jr. /Getty Images

Otto Greule Jr. /Getty ImagesHolmes' abilities brought him acclaim at Carson-Newman and allowed him to become a third-round pick by the Cowboys in 1992.

By the time Clayton turned 13, Phillip -- concerned by one too many tales of neglect -- sued Claudia for custody of his son. A railroad maintenance operator who spent Sundays through Thursdays on the road, Phillip, like Claudia, believed in ruthless discipline. Only, he was significantly stronger than Claudia. "One time I broke into a house, and my dad caught me," Clayton says. "He said to me, 'Clayton, tell me why you did it -- and you better not say you don't know why and you better not cry.'"Clayton started to sob.

POP!

"He punched me in the face with his fist," Clayton says. "Knocked me out cold. But I don't believe he and my mom were intentionally trying to ruin me. It was how they knew to parent … what they were taught by their parents."

If there is a bright side to anger -- to pure, unadulterated anger -- it is that it can be recharged and routed elsewhere. Holmes took the beatings and the mocking and the molestation, and used it to become one of the best athletes in Wilson High School history. He starred as a wishbone quarterback in football, a fleet-footed center fielder in baseball, the school's No. 4 tennis player and one of the two or three best long jumpers South Carolina has ever seen. Because of low test scores and grades in the C-minus range, after Holmes graduated in 1988, he enrolled at North Greenville Junior College, where he led the first-year football program to a 9-1 mark. "He was the best athlete in South Carolina," says Mike Taylor, the North Greenville coach.

"I'll never forget Clayton's explosiveness. It was unparalleled."

Although he has been coaching for 30 years, Taylor still raves over a play from Holmes' sophomore season, when he ran for a 60-yard quarterback sneak with an Aircast guarding a fractured left ankle.

"You gave Clayton the ball," Taylor says, "you knew a touchdown was coming."

While his myriad athletic abilities brought to mind Deion Sanders, Holmes was modest and soft-spoken. He rarely drank, never smoked cigarettes or marijuana, and, recalls his ex-wife, "wouldn't even take a Tylenol."

"Clayton was wonderful," says Lisa, who met Holmes while studying at Carson-Newman, a liberal arts school in Jefferson City, Tenn. "He was very mannerly, very humble. I remember the summer before we started dating, he was at school by himself with no money, no transportation and an empty refrigerator. We're talking about someone who could have starved to death -- but he always saw the bright side."

In two seasons at Carson-Newman, Holmes emerged as the nation's top NAIA cornerback, winning the South Atlantic Conference's Defensive Player of the Year award and earning buzz as a potential sleeper in the '92 draft. On the afternoon of April 26, Holmes sat in his bedroom as family and friends swarmed around the television, anxious to learn who would transform him from broke collegiate nobody to wealthy NFL somebody. When the phone rang, a nervous Clayton picked up.

"Hello?" he said.

"Clayton?"

"Yes."

"This is Jerry Jones from the Dallas Cowboys. How do you feel about wearing a star on your helmet?"

<hr align="left" width="150">It all happened too fast. Holmes can see that now, far removed from the action-packed days and dizzying nights of Dallas. But at the time, in the midst of it all, everything just seemed so … so … right. Dallas Cowboys bought fancy cars, so Clayton Holmes bought fancy cars. Dallas Cowboys bought big houses, so Clayton Holmes bought a big house. Dallas Cowboys flipped $100 bills to exotic dancers, so Clayton Holmes flipped $100 bills to exotic dancers. Following a rookie year during which he tied for second on the club with 15 special teams tackles and had a fumble recovery in the Super Bowl triumph over the Buffalo Bills, Clayton proposed to Lisa, his girlfriend of two years, because, well, that's what he was supposed to do. "I was an adult," he says. "Adults get married."

Only, Holmes wasn't an adult. Oh, his driver's license listed him as 23 years old. But, really, what did he know about being a professional football player? About being a man? About being a husband? One day, you're being molested by your brother in the Florence projects. The next, you're a big-time football player being asked to sign a contract worth more than your family's entire life earnings. "How," Holmes asks, "can that possibly work?" The kid who grew up believing that children were made to be beaten and wives were made to be cheated on and money needed to be spent ASAP was one of hundreds of athletes who have entered professional sports with absolutely no concept of how to live a righteous life. Heck, Holmes had never opened a bank account or written a check. "When I signed my first contract, I was thinking, 'I'm a millionaire! I'm set for life!'" he says of the two-year, $1.3 million deal (featuring a $200,000 signing bonus). A short laugh. "That's how naive I was."

[+] Enlarge

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.com

Jeff Pearlman for ESPN.comOnce again living in his hometown of Florence, S.C., Holmes hopes others can learn from his story.

Long-lost friends and relatives materialized from thin air, smiles wide, palms extended. Although Claudia had largely retreated from her son's life, attending only one of his high school games and none of his collegiate football games, suddenly she was back in the picture. "When Clayton made the NFL, he was her baby again," Phillip says. "I tried to warn him, but he didn't listen." (Says Claudia: "I didn't go to his games because I hated watching him get hit.") Clayton supplied his mother with money, paid off her debts, purchased a new home for her to live in and a car for her to drive. "She wanted a lot," Clayton says, "and was never afraid to ask." (Counters Claudia: "He didn't buy me a house. If he had bought me a house, my name would have been on the paperwork. Yes, I lived in it. But it belonged to Clayton. And the car he bought me only cost $3,000 and was from 1986. Big deal.")On Jan. 9, 1993, Lisa gave birth to the couple's first child, a daughter named Briana. Holmes' initial reaction was, "Run!" He already had a 6-year-old son, Dominique, from a high school girlfriend -- and now this? It was too much. Too real.

Then, the beginning of the end came on Aug. 14, 1993, when Holmes tore ligaments in his right knee during an exhibition game against the Oakland Raiders and learned he would miss the season. Bored and lonely without the sport he loved, he started drinking heavily, smoking pot, cheating on his wife and disappearing for one- and two-day stretches.

When he wasn't home, Holmes often could be found at the strip clubs, hypnotized by the dancers and blowing large wads of money. When, in 1995, he was suspended for one year for testing positive for cocaine, few were surprised. "I never thought of myself as an addict … never felt like I had to have it," he says. "But the drugs relaxed me. I wasn't a person who was comfortable making conversation. But when I was high, people listened to me. The words flowed from my mouth, and I made sense."

In 1995, Lisa took Briana and returned to her hometown of Knoxville, Tenn., leaving Holmes alone with his demons in Dallas. He didn't last long.

Holmes appeared in eight games with the '95 Cowboys, but his drug problems and inconsistent play made him easy to relinquish. Suspended for the entire 1996 season, Holmes signed with the Dolphins in March 1997, after Miami coach Jimmy Johnson called his former player and asked if he was clean.

Holmes said he was.

Holmes wasn't.

That August, he flunked yet another drug test, prompting the Dolphins to release him ("I'm concerned for his future," Johnson told the Tampa Tribune) into the real world. Over the ensuing years, Holmes fathered children with two strippers, underwent substance-abuse and psychological counseling, took a job as a supervisor at the Forbes Juvenile Detention Center in Topeka, Kan., played a season for the Topeka Knights of the Indoor Football League (salary: $200 per game) and, in 1998, moved to Knoxville to be closer to his daughter and ex-wife. It was while living in the Marble City that Holmes plummeted to a new low. His career long dead, his money long gone, his résumé nonexistent (he is 17 credits shy of graduating from college), Clayton was working a low-wage security job. "That's when his mother came to Knoxville and told Clayton she was behind on the mortgage on his house and needed him to pay," Lisa says. "For her to tell him that, well, it was a knife to his heart."

The following afternoon, Holmes swallowed eight Trazodones and closed his eyes. "I wanted to call it quits," he says. "But as I started dozing off, I decided I couldn't go through with it. I guess there was too much to live for." Holmes dialed 911, passed out and woke up the following morning in Peninsula Hospital, a tube stuck down his throat.

<hr align="left" width="150">Three years ago, following mounds of therapy sessions and years of self-reflection, Clayton Holmes decided he needed to return to the place where -- the way he sees it -- Frankenstein's monster was constructed.

He needed to return to Florence.

It has not been pretty.

At first, Holmes' mother and father seemed to support his desire for space and quiet. They kept their distance, letting him sleep when he wanted to sleep, eat when he wanted to eat, talk when he wanted to talk. Now, they are exasperated. "He needs to find a purpose," Phillip says. "Something meaningful." Holmes held a bevy of personal training jobs in the area, but -- like the Super Bowl rings he pawned off -- failed to keep them. He now trains five clients per week at the local high school, charging $25 an hour.

At his best, Holmes is kind, charming and well-intentioned. When the 12-year-old son of a cousin recently admired two of his old NFL jerseys, Holmes whipped the garments out of a cardboard box and handed them over. "They were his last two jerseys," says Travis Hunter, the cousin. "He insisted, 'Take them, take them, take them.' People say, 'So-and-so would give you the shirt off his back,' and it's always a cliche. But Clayton will literally give you everything you need."

Yet, Holmes remains an enigma. When he is not riding his bicycle, he spends most of his days holed up in his hovel, jotting thoughts into a spiral notepad, or writing songs and recording them into a microcassette recorder, or planning a potential move to Washington, D.C., where he wants to immerse himself in Scientology. Although he owes more than $2,500 per month in child support, he is unmoved to find work at, say, the local Holiday Inn or Burger King.

"Here's the truth," he says. "Most fathers would be like, 'I have to take care of my kids, and it doesn't matter how I go about that.' I don't have that drive. I'm just being honest -- it's not there for me. I feel a connection with my kids but not an urgency."

Holmes takes a deep breath. He is wrong, and he knows it.

"I have not been a good father to my children. I was a lousy husband.

"But that's why I want to be heard. I'm part of a long line of people who think and act just like I do. The people who raised me tried to do right, but they knew no better. It needs to stop. It has to stop.

"Parents have to love and cherish and look out for their kids, or else they're gonna wind up just like me."

Another pause.

"Like me," he says. "Lost."

Jeff Pearlman is a former Sports Illustrated senior writer and the author of "Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero," now available in paperback. You can reach him at anngold22@gmail.com.