Walking the line

Corner bookie Floyd Fielding makes his living the old-fashioned way: One loser at a time

<cite class="source">By Tim Struby

ESPN The Magazine

http://search.espn.go.com/tim-struby/</cite>

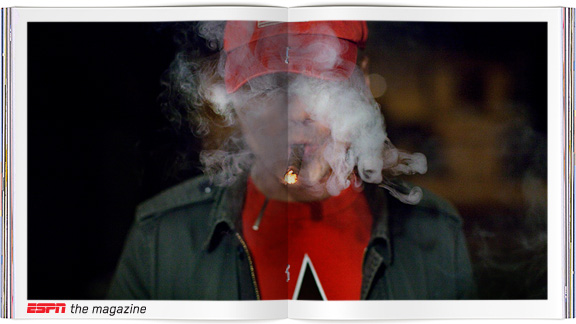

<cite>Jessica Dimmock/VII</cite>Sometimes a cigarillo is just a cigarillo. But not when that cigarillo is being smoked by a bookie to mask his identity. For Fielding, a smoke screen is all that stands between him, identification and prosecution.

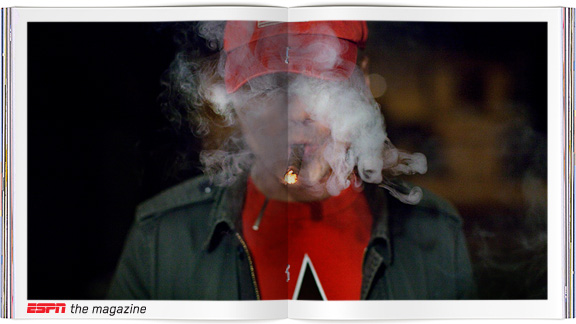

<cite>Jessica Dimmock/VII</cite>Sometimes a cigarillo is just a cigarillo. But not when that cigarillo is being smoked by a bookie to mask his identity. For Fielding, a smoke screen is all that stands between him, identification and prosecution.

This story appears in the March 5, 2012 "Analytics Issue" of ESPN The Magazine. Subscribe today!

IN THE NEON glow of Manhattan's Times Square, a black sedan glides through the streets. At the wheel sits Floyd Fielding*, armed with his essentials: cigarillo, Uni-ball pen clipped to his T-shirt, four cellphones at the ready. On this Tuesday night in November, he'll make eight stops from Battery Park to the Upper West Side. He does not speed or text while moving. He drives cautiously -- not only because of the pre-holiday crowds but because Fielding, by the nature of his business, is a cautious man.

Terms you'll need to know for this story

<table> <tbody> <tr class="last oddrow"> <td>DIME</td> <td>Gambling shorthand for $1,000.</td> </tr> <tr class="last evenrow"> <td>SETTLE-UP NUMBER</td> <td>The predetermined level of a client's tally -- up or down -- at which a bookie pays out or collects.</td> </tr> <tr class="last oddrow"> <td>SYNDICATE</td> <td>A collection of professional gamblers that pools its efforts in an attempt to beat the sportsbooks.</td> </tr> <tr class="last evenrow"> <td>VIGORISH</td> <td>The commission bookies charge clients to place a bet.</td> </tr> </tbody> </table>

After parking in front of an Irish pub, he pulls an 8-by-6 index card from his jacket and scans several rows of hand-scrawled names. He grabs an envelope, a standard No. 10 white-wove envelope that he buys in boxes of 500 from Staples. He double-checks its contents -- six hundred-dollar bills -- and crosses a name off the card. He gives a listen to the Duke-Michigan State game on the radio. He doesn't care that a Duke victory will make Coach K the winningest coach in men's college basketball history. He's concerned only with the score: Midway through the second half, the Blue Devils are up 20. He's got a "couple of bucks" riding on the outcome -- in Fielding-speak, somewhere from $1,000 to $5,000.

"At least I'll win this game," he says, confident Duke will cover the seven-point spread. For the past 14 years, Fielding has made a living passing envelopes -- in the back rooms of bars, in crowded restaurants, on city sidewalks and behind tinted car windows. He's not a violent thug or a member of organized crime. He's a 41-year-old independent one-man bookmaker. And business is booming.

Fielding spends precisely 50 seconds inside the pub. Over the next hour and a half, he'll stop at three midtown pubs, a West Side bar, a posh Upper East Side prep school (to collect from a custodian), a Murray Hill walk-up and a waterfront penthouse. He operates with the efficiency of a deliveryman on a Boar's Head route. The only difference is the guy dropping off Virginia ham isn't picking up $25,000.

Around midnight, Fielding crosses the last name off his index card and turns his attention back to the radio. He hears celebrating, talk of Coach K's record-setting 903rd win. But his smile turns to a sneer when he hears the 74-69 final score. Fielding scoffs, then puts the car in drive. "Didn't even cover the points," he says.

<center><hr style="width:50%;"></center>SUNDAY MORNING, and little stirs in Fielding's neighborhood. It's a tree-lined block an hour outside of New York City, with aluminum siding and aboveground pools. Its residents, like Fielding, are second- and third-generation immigrants -- Italian, Irish, German, Polish.

Corner bookie Floyd Fielding makes his living the old-fashioned way: One loser at a time

<cite class="source">By Tim Struby

ESPN The Magazine

http://search.espn.go.com/tim-struby/</cite>

This story appears in the March 5, 2012 "Analytics Issue" of ESPN The Magazine. Subscribe today!

IN THE NEON glow of Manhattan's Times Square, a black sedan glides through the streets. At the wheel sits Floyd Fielding*, armed with his essentials: cigarillo, Uni-ball pen clipped to his T-shirt, four cellphones at the ready. On this Tuesday night in November, he'll make eight stops from Battery Park to the Upper West Side. He does not speed or text while moving. He drives cautiously -- not only because of the pre-holiday crowds but because Fielding, by the nature of his business, is a cautious man.

Terms you'll need to know for this story

<table> <tbody> <tr class="last oddrow"> <td>DIME</td> <td>Gambling shorthand for $1,000.</td> </tr> <tr class="last evenrow"> <td>SETTLE-UP NUMBER</td> <td>The predetermined level of a client's tally -- up or down -- at which a bookie pays out or collects.</td> </tr> <tr class="last oddrow"> <td>SYNDICATE</td> <td>A collection of professional gamblers that pools its efforts in an attempt to beat the sportsbooks.</td> </tr> <tr class="last evenrow"> <td>VIGORISH</td> <td>The commission bookies charge clients to place a bet.</td> </tr> </tbody> </table>

After parking in front of an Irish pub, he pulls an 8-by-6 index card from his jacket and scans several rows of hand-scrawled names. He grabs an envelope, a standard No. 10 white-wove envelope that he buys in boxes of 500 from Staples. He double-checks its contents -- six hundred-dollar bills -- and crosses a name off the card. He gives a listen to the Duke-Michigan State game on the radio. He doesn't care that a Duke victory will make Coach K the winningest coach in men's college basketball history. He's concerned only with the score: Midway through the second half, the Blue Devils are up 20. He's got a "couple of bucks" riding on the outcome -- in Fielding-speak, somewhere from $1,000 to $5,000.

"At least I'll win this game," he says, confident Duke will cover the seven-point spread. For the past 14 years, Fielding has made a living passing envelopes -- in the back rooms of bars, in crowded restaurants, on city sidewalks and behind tinted car windows. He's not a violent thug or a member of organized crime. He's a 41-year-old independent one-man bookmaker. And business is booming.

Fielding spends precisely 50 seconds inside the pub. Over the next hour and a half, he'll stop at three midtown pubs, a West Side bar, a posh Upper East Side prep school (to collect from a custodian), a Murray Hill walk-up and a waterfront penthouse. He operates with the efficiency of a deliveryman on a Boar's Head route. The only difference is the guy dropping off Virginia ham isn't picking up $25,000.

Around midnight, Fielding crosses the last name off his index card and turns his attention back to the radio. He hears celebrating, talk of Coach K's record-setting 903rd win. But his smile turns to a sneer when he hears the 74-69 final score. Fielding scoffs, then puts the car in drive. "Didn't even cover the points," he says.

<center><hr style="width:50%;"></center>SUNDAY MORNING, and little stirs in Fielding's neighborhood. It's a tree-lined block an hour outside of New York City, with aluminum siding and aboveground pools. Its residents, like Fielding, are second- and third-generation immigrants -- Italian, Irish, German, Polish.