<hgroup class="header2" style="display: block;">[h=1]The Match Maker[/h][h=2]Bobby Riggs, The Mafia and The Battle of the Sexes[/h]Outside the Lines

by Don Van Natta Jr.ILLUSTRATION BY JOSUE EVILLA

<time>08/25/13</time>

</hgroup> "HELLO AGAIN EVERYONE, I'm Howard Cosell. We're delighted to be able to bring you this very, very quaint, unique event."

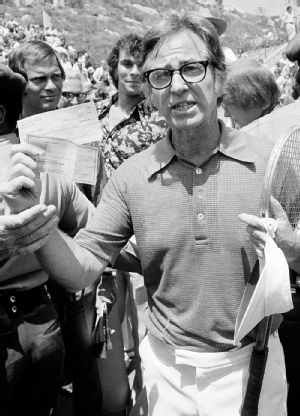

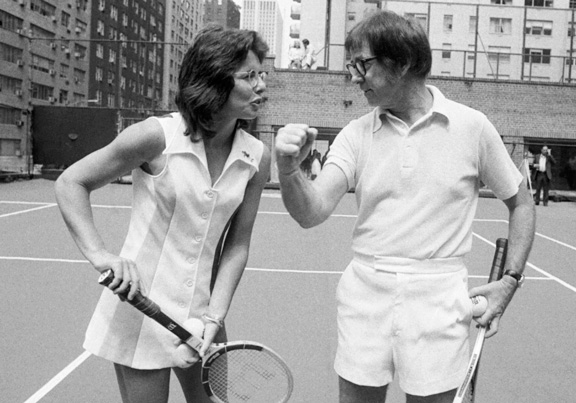

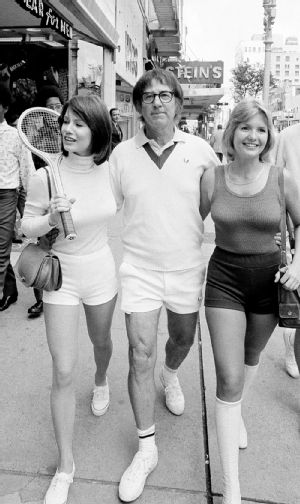

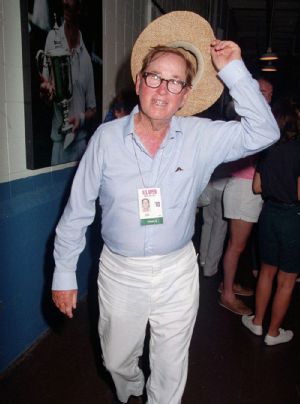

On Thursday night, Sept. 20, 1973, 50 million Americans, fatigued by Vietnam and Watergate, tuned in to see whether a woman could defeat a man on a tennis court. Dubbed "The Battle of the Sexes," the match pitted Billie Jean King, the 29-year-old champion of that summer's Wimbledon and a crusader for the women's liberation movement, against Bobby Riggs, the 55-year-old gambler, hustler and long-ago tennis champ who had willingly become America's bespectacled caricature of male chauvinism.

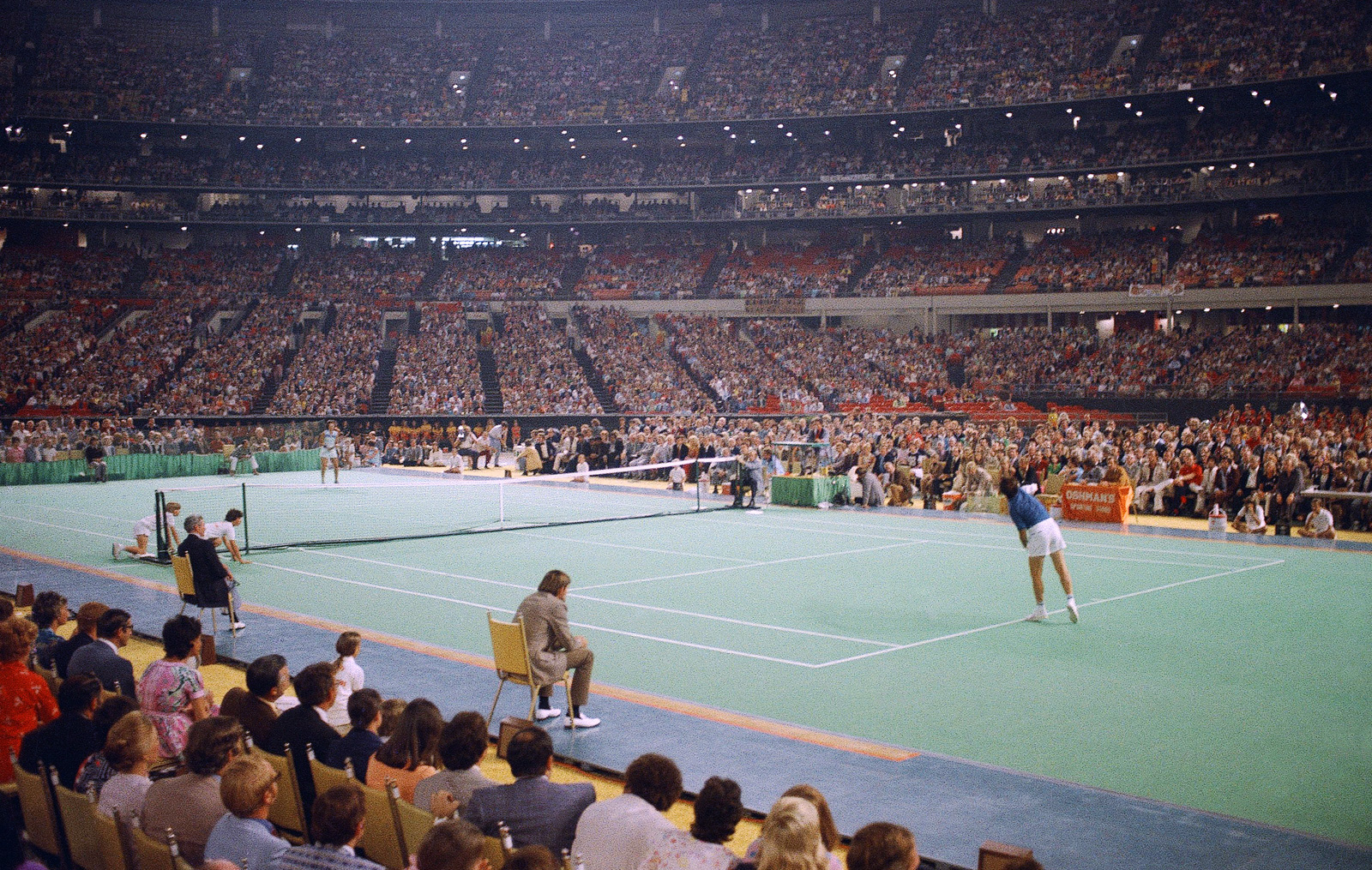

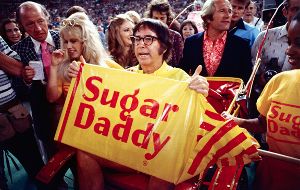

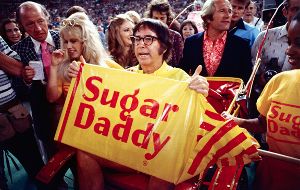

Before 30,472 at the Houston Astrodome, still the largest crowd to watch tennis in the United States, the spectacle felt like a cross between a heavyweight championship bout and an old-time tent revival. Flanked by bikini-clad young women, Riggs, in a canary yellow Sugar Daddy warm-up jacket, was imperiously carted into the Astrodome aboard a gilded rickshaw. Not to be outdone, King, wearing a blue-and-white sequined tennis dress, sat like Cleopatra in a chariot delivered courtside by bare-chested, muscle-ripped young men. Moments before the first serve, King presented Riggs with a squealing, squirming piglet. "Look at that male chauvinist pig," Cosell told viewers. "That symbolizes what Bobby Riggs is holding up. ..."

Enlarge

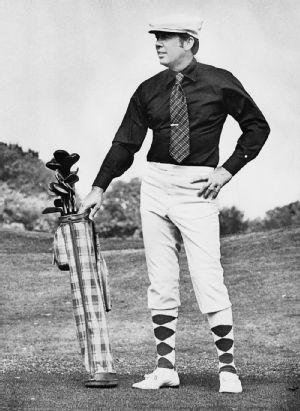

The Sugar Daddy sign and warm-up jacket Bobby Riggs wore during "The Battle of the Sexes" earned him money and added to the match's spectacle. Bettmann/CORBIS

The Sugar Daddy sign and warm-up jacket Bobby Riggs wore during "The Battle of the Sexes" earned him money and added to the match's spectacle. Bettmann/CORBIS

Gallery

[h=5]Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs[/h] Battle of the Sexes Focus on Sport/Getty Images

All of the vaudevillian hoopla made it easy to forget the enormous stakes and the far-reaching social consequences. King was playing not just for public acceptance of the women's game but also an opportunity to prove her gender's equality at a time when women could still not obtain a credit card without a man's signature. If she were to defeat Bobby Riggs, the triumph would be shared by every woman who knew she deserved equal pay, opportunities and respect. Equally sweet, King would cram shut the mouth of a male chauvinist clown who had chortled that a woman belonged in the bedroom and the kitchen but certainly not in the same arena competing against a man. For Riggs, the $100,000 winner-take-all match offered big money and a perfect launching pad to a late-in-life career playing exhibition matches against women.

It seemed a certain payday for him. Four months earlier, Riggs had crushed Margaret Court, the world's No. 1 women's tennis player, 6-2, 6-1, in an exhibition labeled by the media as the "Mother's Day Massacre." Court's defeat had persuaded King to play Riggs. Nearly everyone in tennis expected a similarly lopsided result. On the ABC broadcast, Pancho Gonzales, John Newcombe and even 18-year-old Chrissie Evert predicted Riggs would defeat King, then the No. 2-ranked woman. In Las Vegas, the smart money was on Bobby Riggs. Jimmy the Greek declared, "King money is scarce. It's hard to find a bet on the girl."

But by aggressively attacking the net and smashing precision shots, King ran a winded, out-of-shape Riggs all over the court. Riggs made a slew of unforced errors, hitting soft returns directly at King or into the net and double-faulting at key moments, including on set point in the first set. "I don't understand," Cosell said after a King winner off a Riggs backhand. "He's been feeding her that backhand all night." Midway through the third set, Riggs looked drained and complained of hand cramps. After King took match point, winning in straight sets, 6-4, 6-3, 6-3, Riggs mustered the energy to hop the net. "I underestimated you," he whispered in King's ear.

Several hours later, Bobby Riggs lay in an ice bath in the Tarzan Room of Houston's AstroWorld Hotel. Despondent and alone, Riggs contemplated lowering his head into the icy water and drowning himself.

"This was the worst thing in the world I've ever done," Bobby Riggs later told his son, Larry, about his defeat before the whole world. "The worst thing I've ever done."

by Don Van Natta Jr.ILLUSTRATION BY JOSUE EVILLA

<time>08/25/13</time>

</hgroup> "HELLO AGAIN EVERYONE, I'm Howard Cosell. We're delighted to be able to bring you this very, very quaint, unique event."

On Thursday night, Sept. 20, 1973, 50 million Americans, fatigued by Vietnam and Watergate, tuned in to see whether a woman could defeat a man on a tennis court. Dubbed "The Battle of the Sexes," the match pitted Billie Jean King, the 29-year-old champion of that summer's Wimbledon and a crusader for the women's liberation movement, against Bobby Riggs, the 55-year-old gambler, hustler and long-ago tennis champ who had willingly become America's bespectacled caricature of male chauvinism.

Before 30,472 at the Houston Astrodome, still the largest crowd to watch tennis in the United States, the spectacle felt like a cross between a heavyweight championship bout and an old-time tent revival. Flanked by bikini-clad young women, Riggs, in a canary yellow Sugar Daddy warm-up jacket, was imperiously carted into the Astrodome aboard a gilded rickshaw. Not to be outdone, King, wearing a blue-and-white sequined tennis dress, sat like Cleopatra in a chariot delivered courtside by bare-chested, muscle-ripped young men. Moments before the first serve, King presented Riggs with a squealing, squirming piglet. "Look at that male chauvinist pig," Cosell told viewers. "That symbolizes what Bobby Riggs is holding up. ..."

Enlarge

Gallery

[h=5]Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs[/h] Battle of the Sexes Focus on Sport/Getty Images

All of the vaudevillian hoopla made it easy to forget the enormous stakes and the far-reaching social consequences. King was playing not just for public acceptance of the women's game but also an opportunity to prove her gender's equality at a time when women could still not obtain a credit card without a man's signature. If she were to defeat Bobby Riggs, the triumph would be shared by every woman who knew she deserved equal pay, opportunities and respect. Equally sweet, King would cram shut the mouth of a male chauvinist clown who had chortled that a woman belonged in the bedroom and the kitchen but certainly not in the same arena competing against a man. For Riggs, the $100,000 winner-take-all match offered big money and a perfect launching pad to a late-in-life career playing exhibition matches against women.

It seemed a certain payday for him. Four months earlier, Riggs had crushed Margaret Court, the world's No. 1 women's tennis player, 6-2, 6-1, in an exhibition labeled by the media as the "Mother's Day Massacre." Court's defeat had persuaded King to play Riggs. Nearly everyone in tennis expected a similarly lopsided result. On the ABC broadcast, Pancho Gonzales, John Newcombe and even 18-year-old Chrissie Evert predicted Riggs would defeat King, then the No. 2-ranked woman. In Las Vegas, the smart money was on Bobby Riggs. Jimmy the Greek declared, "King money is scarce. It's hard to find a bet on the girl."

But by aggressively attacking the net and smashing precision shots, King ran a winded, out-of-shape Riggs all over the court. Riggs made a slew of unforced errors, hitting soft returns directly at King or into the net and double-faulting at key moments, including on set point in the first set. "I don't understand," Cosell said after a King winner off a Riggs backhand. "He's been feeding her that backhand all night." Midway through the third set, Riggs looked drained and complained of hand cramps. After King took match point, winning in straight sets, 6-4, 6-3, 6-3, Riggs mustered the energy to hop the net. "I underestimated you," he whispered in King's ear.

Several hours later, Bobby Riggs lay in an ice bath in the Tarzan Room of Houston's AstroWorld Hotel. Despondent and alone, Riggs contemplated lowering his head into the icy water and drowning himself.

"This was the worst thing in the world I've ever done," Bobby Riggs later told his son, Larry, about his defeat before the whole world. "The worst thing I've ever done."