[h=1]Editor's Note: This article was published prior to learning about the charges against Adrian Peterson.

Sometimes an NFL play is so good, defenses know it's coming and still can't stop it.

Which plays in today's NFL qualify as so strong and so counterbalanced within a game plan that defenses are presented with nothing but bad options? That's my task here: sort through hours of game film and find the five most truly "unstoppable" plays.

Now, in some cases I'm using the term "play" fairly loosely. I don't necessarily mean exactly what the thing is called in the playbook, and often I'm grouping multiple plays under one umbrella concept. The goal here is to get a holistic sense of some truly nasty offensive weapons that defenses have no chance of stopping.

Here's my list, in reverse order of unstoppability:

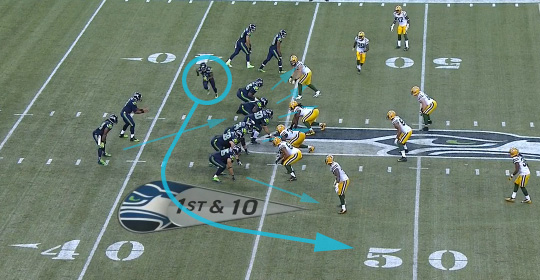

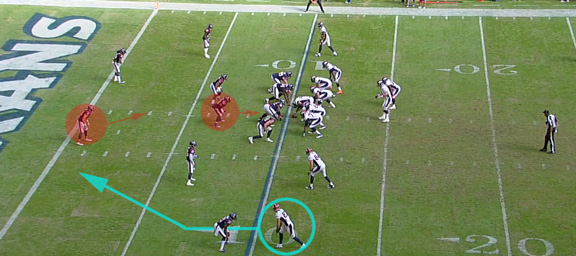

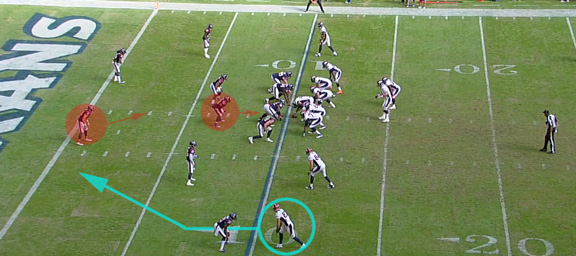

Thursday night, the Seahawks used a variation on this jet sweep:<offer></offer>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

The concept is the same: Get Harvin the ball at full speed with the defense leaning the other way. In this case, Wilson is in the shotgun. He sets Harvin in motion, receives the snap and activates Lynch in a read-option look. The offensive line blocks left, giving the Green Bay Packers' front seven an indication that this is a zone run to that side. But Zach Miller sprints right, tasked with holding off safety Morgan Burnett until Harvin can sprint around him. This play gained 16 yards; the Seahawks ran this play for Harvin another time Thursday night, and that time it gained 13 yards.

Why it's unstoppable: The play's effectiveness begins with Harvin. He's so fast and decisive as a runner, and so flexible that he can change directions while on the dead run without losing momentum. Of course, the NFL has many fast players. This one works because it puts the defense between a rock and a hard place.

The Seahawks run the zone read as well as any team west of Philadelphia (see No. 2 below), with an agile offensive line full of players adept at getting blocks at a defense's second level when they're uncovered at the snap. This often provides Lynch with huge cutback lanes, and Lynch himself is a handful to tackle in the open field. When a defense sees Seattle's linemen charge out left, its tendency is to anticipate a zone run and plug gaps. By sending Harvin in motion through the backfield, the Seahawks are requiring the defense to stay honest on the back side, something that's difficult to do when Lynch has worn you down all game.

Lean too heavily Lynch's way? Wilson will give it to Harvin. Cheat for the jet sweep? Lynch winds up with the rock, and you suffer more Beast Mode.

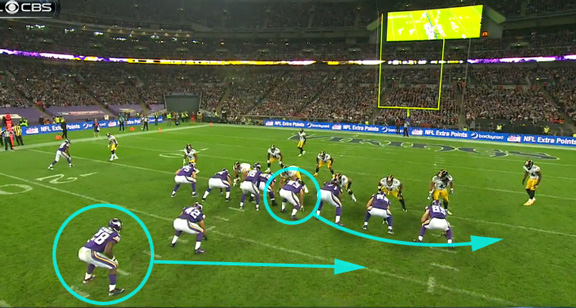

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

RG Brandon Fusco, a 2011 sixth-rounder, has become a mauler in the run game, and he is particularly effective in combination with RT Phil Loadholt, one of the NFL's best run-blockers over the past three seasons. The Vikings don't always run this play with two tight ends; in fact, they occasionally make it work with a single tight end lined up on the left. Certainly, thePittsburgh Steelers are reading sweep here (the play was third-and-short), but they can't stop All Day. Loadholt and the TEs fire out straight, Fusco comes around the edge and crushes a DB, and Peterson gains 9 yards.

Why it's unstoppable: First and foremost, it's because Peterson is a Hall of Famer. He's capable of breaking to the second level using nearly any kind of run design, and once he's at full speed he avoids or overpowers men his size or smaller. But the reason this particular play is so effective is that defenses have to respect the straight-ahead stuff. The Vikings aren't typically a finesse-blocking squad. They use a lead blocker and power straight ahead, relying on Peterson's start/stop and lateral agility to weave through traffic at the point of attack. So when they read run, defensive linemen become intent on holding their ground, and linebackers are thinking "north-south" more than they're thinking "east-west."

In cases like this when the Vikings get AP running laterally before exploding upfield, it's a change of pace that feels like a punch to the mouth. Yes, such lateral runs can occasionally get stuffed when the wrong defensive penetrator gets upfield. But if defenses cheat for a sweep, they're apt to get run over by a Peterson lead draw.

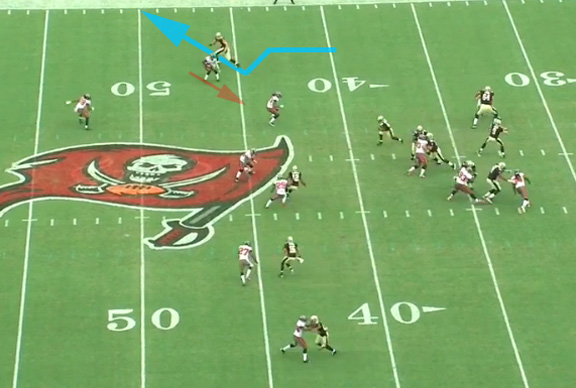

Of all the stuff the Saints run for Graham, the best thing they do is the 7-8-9 combination, which is to say: Graham runs straight off the line and either keeps going (9-route), goes to the post (8-route) or goes to the corner (7-route). He can do this from inline, in the slot or out wide, and many of Drew Brees' audibles involve looking at who's matched up with Graham and switching to an appropriate play. If Brees reads zone, Graham will settle between LBs and DBs. If he gets man coverage on a safety out wide, it's jump-ball time. And sometimes, when Brees and Graham are feeling particularly vindictive, they'll check to this piece of nastiness:

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

Graham began this play, from last season, inline, and, as Lance Moore motioned to the strong side, Graham split wide. Then he ran a filthy post-corner on which CB Ahmad Black bit, allowing Graham an effortless 23-yard gain.

Why it's unstoppable: What do you do with a 6-foot-7, 265-pound monster who can run seam and corner routes as effortlessly as he runs cross or stick routes? Do you shadow him with a single defender? Do you try to maul him at the line? Do you zone the Saints and just try to keep Graham in front of you? Essentially, the answer is that unless you have a freaky-fast cover linebacker such as Lavonte David or Bobby Wagner, you probably mix up all of these strategies and hope you can contain Graham and/or distract Brees into using other weapons.

In Week 1, the Atlanta Falcons often had Dwight Lowery or Robert McClain hovering in front of Graham, willing to give up the short stuff, and they always redirected him with a chuck at the line (and sometimes beyond the legal 5-yard area). Despite all this attention, Graham still registered eight catches for 82 yards. His physical dominance and agility make him so unstoppable that 8-for-82 counts as "containing" Graham.

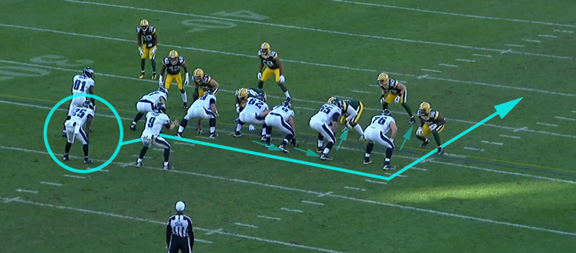

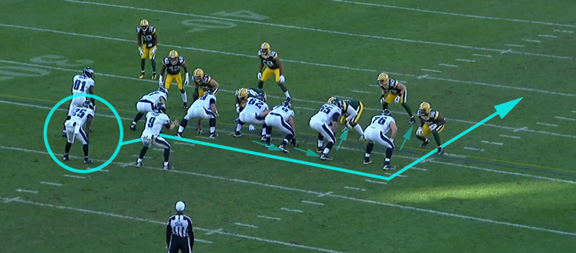

Shady won his first rushing title last year and led the league in combined yards from scrimmage. Chip Kelly's offense is wildly varied, but it's largely based on zone runs: ThePhiladelphia Eagles had 304 zone-read carries in '13, and the Buffalo Bills were second with 169. Many of these carries were of the inside-zone variety in which the Eagles let Shady get north-south, often with a false read-option movement by QB Nick Foles. This is bread-and-butter stuff that keeps the chains moving. But it's on outside-zone runs that McCoy breaks games open:

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

On this play, center Jason Kelce and right guard Todd Herremans are uncovered, so they run for the right sideline and mash whatever is in their way. (Right tackle Lane Johnson and extra tackle Allen Barbre are covered, so their assignment is simply to block their men, to the inside if possible.) McCoy takes an inside handoff and runs east-west, with the intent of heading around right tackle. Anytime he sees a crease, he can cut upfield, but on this play Shady sprinted to the edge and found daylight to the tune of a 30-yard gain.

Outside-zone runs take longer to develop, which implies they can be blown up more easily than the north-south inside plays. But Kelly will stick with these stretch zone runs, knowing McCoy is just waiting for his chance to flaunt his insane quickness on a big gainer.

Why it's unstoppable: Unstoppable plays always start with the skill of the highlighted player, and McCoy is the NFL's quickest RB, bar none. In particular, the stretch zone suits McCoy so well because it affords him the opportunity to glide toward the sideline and observe how the defense reacts, then put thought into action when he sees daylight by changing direction and accelerating to top speed.

The biggest defensive danger here is over-pursuit. It isn't difficult for linebackers and safeties to sniff these plays out as a variety of sweep, and their instinct is to beat blockers to the point and try to meet Shady at the spot he appears to be heading. If the defense is too aggressive, of course, Shady will simply cut back to the vacant lane. Yet, if the defense isn't aggressive enough, McCoy runs around the edge, as he did in the play I highlighted above. In Week 1, the Eagles suffered a couple of significant injuries on their offensive line, and they might have to start journeyman Andrew Gardner at right tackle Sunday. If that happens, we'll get a look at how unstoppable this scheme really is. (Or the Eagles will simply do nothing but run left ...)

The 2013 Broncos boasted the most prolific offense in NFL history, setting single-season records for the most points, most passing yards and most passing TDs. There is, of course, a nearly infinite number of formation and route combinations that the Sheriff is able to process quicker than any man alive, and that means he can get away with subpar arm strength here in his NFL dotage. He's smart enough to conquer your army with a popgun.

The "play" I'm talking about here isn't as much a single route combination as a series of reads whereby Manning diagnoses a defense's plan before it can begin. His legendary pre-snap routine no doubt contains much jabberwocky, but he also signals which option he wants each receiver to enact. Manning's decision-making tree isn't immensely complicated. Speaking very generally, it goes like this:

• If the defense indicates it will fall into Cover 2, he'll ask Julius Thomas or one of his outside receivers to run a cross or sit down between zone defenders in the middle.

• If the defense shows Cover 3 or another single-safety-high defense (such as Cover 1 or Cover 1 robber), he's likely to call for vertical routes and play-action, to catch the back seven cheating forward and loop a throw, especially to the deep corners.

• If the defense plays its corners off, he'll check to a bubble or tunnel screen.

• If the defense shows straight man, someone is going deep.

Of course, these rules aren't absolute, plus this is pretty much the blueprint by which most veteran pocket QBs live. But Manning is able to orchestrate these reactive options out of any play called in the huddle, and what's most amazing is how often he's right:

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

<cite style="margin: 0px 0px 4px; padding: 0px; border: 0px; outline: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; display: block; color: rgb(171, 171, 171); background: transparent;">Christopher Harris</cite>

Here, in a play from last season, Manning sees something in linebacker Joe Mays' posture that gives away some kind of blitz or swap in responsibility for covering Knowshon Moreno out of the backfield. Manning begins gesturing, changing the play. He knows safety Shiloh Keo will favor the inside at the snap, seeking to replace Mays by helping with Jacob Tamme in the slot. This leaves Eric Decker one-on-one on an in-breaking route versus Brice McCain, which Manning knows Decker can win. He communicates this option to Decker, then fires the slant for a TD. He knew what he'd have before the ball even snapped, apparently because of Mays' posture.

Why it's unstoppable: It's not about the weapons. Yes, it helps that Julius Thomas andDemaryius Thomas, Wes Welker, and Emmanuel Sanders are big-time weapons in the passing game. But watch the tape and you'll see how relatively infrequently a Broncos target has a defender anywhere near him. Manning throws to wide-open receivers more than any other NFL QB, and not only because his guys run good routes. He has simply chosen (and signaled) the right option before the play even begins.

So what did the Seahawks do in the Super Bowl? They didn't really scheme Manning. They mostly played a single safety high and zoned the Broncos, didn't blitz much and relied on rotational fronts to pressure Manning enough so his preferred deep routes didn't have time to develop. Against a Seattle zone filled with incredibly athletic linebackers and safeties who "spot-dropped" to prescribed locales to clog the deep and intermediate middle, Manning hit some short passes but then got out of sorts, and as the scoreboard got lopsided, he forced a few poor throws. Most defenses simply don't have the personnel to pull this off, which is why Manning will continue to be an audible-option machine in '14.

[/h]

Sometimes an NFL play is so good, defenses know it's coming and still can't stop it.

Which plays in today's NFL qualify as so strong and so counterbalanced within a game plan that defenses are presented with nothing but bad options? That's my task here: sort through hours of game film and find the five most truly "unstoppable" plays.

Now, in some cases I'm using the term "play" fairly loosely. I don't necessarily mean exactly what the thing is called in the playbook, and often I'm grouping multiple plays under one umbrella concept. The goal here is to get a holistic sense of some truly nasty offensive weapons that defenses have no chance of stopping.

Here's my list, in reverse order of unstoppability:

[/h][h=3]5. Percy Harvin's jet sweep[/h][h=1]He can be a frustrating player because he's been injured so often, but Harvin's game-changing chops were on display in Week 1's Thursday night opener. The Seattle Seahawks reintroduced Harvin to the NFL in last year's Super Bowl, sending him in motion with Russell Wilson under center, giving the appearance of a typical zone run to Marshawn Lynch but sneaking the ball to Harvin on a narrow end-around. Harvin ran this play twice against the Denver Broncos that day and gained 45 yards, and later had the Broncos so paranoid that he opened up more lanes for Lynch simply by going in motion.Thursday night, the Seahawks used a variation on this jet sweep:<offer></offer>

The concept is the same: Get Harvin the ball at full speed with the defense leaning the other way. In this case, Wilson is in the shotgun. He sets Harvin in motion, receives the snap and activates Lynch in a read-option look. The offensive line blocks left, giving the Green Bay Packers' front seven an indication that this is a zone run to that side. But Zach Miller sprints right, tasked with holding off safety Morgan Burnett until Harvin can sprint around him. This play gained 16 yards; the Seahawks ran this play for Harvin another time Thursday night, and that time it gained 13 yards.

Why it's unstoppable: The play's effectiveness begins with Harvin. He's so fast and decisive as a runner, and so flexible that he can change directions while on the dead run without losing momentum. Of course, the NFL has many fast players. This one works because it puts the defense between a rock and a hard place.

The Seahawks run the zone read as well as any team west of Philadelphia (see No. 2 below), with an agile offensive line full of players adept at getting blocks at a defense's second level when they're uncovered at the snap. This often provides Lynch with huge cutback lanes, and Lynch himself is a handful to tackle in the open field. When a defense sees Seattle's linemen charge out left, its tendency is to anticipate a zone run and plug gaps. By sending Harvin in motion through the backfield, the Seahawks are requiring the defense to stay honest on the back side, something that's difficult to do when Lynch has worn you down all game.

Lean too heavily Lynch's way? Wilson will give it to Harvin. Cheat for the jet sweep? Lynch winds up with the rock, and you suffer more Beast Mode.

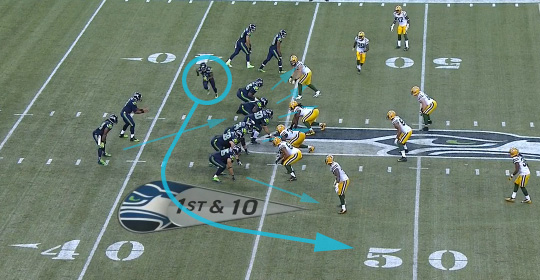

[/h][h=3]4. Adrian Peterson running right, behind a front-side pulling guard[/h][h=1]Peterson has played seven NFL seasons and has never failed to score double-digit TDs. You don't need me to tell you he's great, and it would be folly to suggest his incredible production is the result of scheme. AP has a rare combination of speed, quickness and power that would help him succeed no matter the system. But lately the Minnesota Vikings have found something that works exceedingly well (screenshot from last season):

RG Brandon Fusco, a 2011 sixth-rounder, has become a mauler in the run game, and he is particularly effective in combination with RT Phil Loadholt, one of the NFL's best run-blockers over the past three seasons. The Vikings don't always run this play with two tight ends; in fact, they occasionally make it work with a single tight end lined up on the left. Certainly, thePittsburgh Steelers are reading sweep here (the play was third-and-short), but they can't stop All Day. Loadholt and the TEs fire out straight, Fusco comes around the edge and crushes a DB, and Peterson gains 9 yards.

Why it's unstoppable: First and foremost, it's because Peterson is a Hall of Famer. He's capable of breaking to the second level using nearly any kind of run design, and once he's at full speed he avoids or overpowers men his size or smaller. But the reason this particular play is so effective is that defenses have to respect the straight-ahead stuff. The Vikings aren't typically a finesse-blocking squad. They use a lead blocker and power straight ahead, relying on Peterson's start/stop and lateral agility to weave through traffic at the point of attack. So when they read run, defensive linemen become intent on holding their ground, and linebackers are thinking "north-south" more than they're thinking "east-west."

In cases like this when the Vikings get AP running laterally before exploding upfield, it's a change of pace that feels like a punch to the mouth. Yes, such lateral runs can occasionally get stuffed when the wrong defensive penetrator gets upfield. But if defenses cheat for a sweep, they're apt to get run over by a Peterson lead draw.

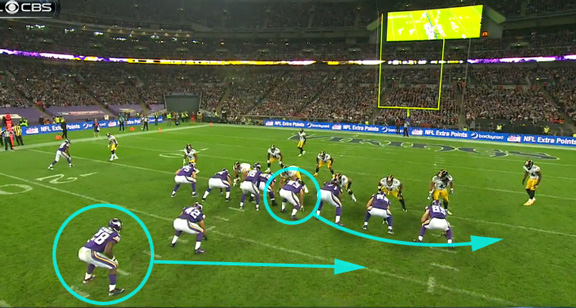

[/h][h=3]3. Jimmy Graham: option routes[/h][h=1]I'm spinning this one on its head, because Graham doesn't create his particular brand of havoc by running the same play again and again. Rather, because he's so adept at running such a wide variety of routes, he has the ability to beat almost any kind of defender playing almost any kind of alignment. And the New Orleans Saints employ him all over their formation specifically with the idea of reacting and running option routes based on what they see from a defense.Of all the stuff the Saints run for Graham, the best thing they do is the 7-8-9 combination, which is to say: Graham runs straight off the line and either keeps going (9-route), goes to the post (8-route) or goes to the corner (7-route). He can do this from inline, in the slot or out wide, and many of Drew Brees' audibles involve looking at who's matched up with Graham and switching to an appropriate play. If Brees reads zone, Graham will settle between LBs and DBs. If he gets man coverage on a safety out wide, it's jump-ball time. And sometimes, when Brees and Graham are feeling particularly vindictive, they'll check to this piece of nastiness:

Graham began this play, from last season, inline, and, as Lance Moore motioned to the strong side, Graham split wide. Then he ran a filthy post-corner on which CB Ahmad Black bit, allowing Graham an effortless 23-yard gain.

Why it's unstoppable: What do you do with a 6-foot-7, 265-pound monster who can run seam and corner routes as effortlessly as he runs cross or stick routes? Do you shadow him with a single defender? Do you try to maul him at the line? Do you zone the Saints and just try to keep Graham in front of you? Essentially, the answer is that unless you have a freaky-fast cover linebacker such as Lavonte David or Bobby Wagner, you probably mix up all of these strategies and hope you can contain Graham and/or distract Brees into using other weapons.

In Week 1, the Atlanta Falcons often had Dwight Lowery or Robert McClain hovering in front of Graham, willing to give up the short stuff, and they always redirected him with a chuck at the line (and sometimes beyond the legal 5-yard area). Despite all this attention, Graham still registered eight catches for 82 yards. His physical dominance and agility make him so unstoppable that 8-for-82 counts as "containing" Graham.

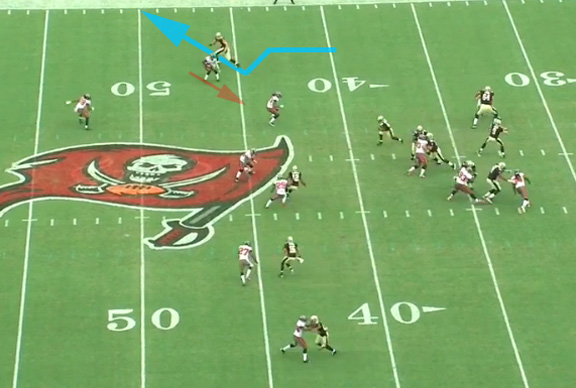

[/h][h=3]2. LeSean McCoy's outside-zone runs[/h][h=1]Shady won his first rushing title last year and led the league in combined yards from scrimmage. Chip Kelly's offense is wildly varied, but it's largely based on zone runs: ThePhiladelphia Eagles had 304 zone-read carries in '13, and the Buffalo Bills were second with 169. Many of these carries were of the inside-zone variety in which the Eagles let Shady get north-south, often with a false read-option movement by QB Nick Foles. This is bread-and-butter stuff that keeps the chains moving. But it's on outside-zone runs that McCoy breaks games open:

On this play, center Jason Kelce and right guard Todd Herremans are uncovered, so they run for the right sideline and mash whatever is in their way. (Right tackle Lane Johnson and extra tackle Allen Barbre are covered, so their assignment is simply to block their men, to the inside if possible.) McCoy takes an inside handoff and runs east-west, with the intent of heading around right tackle. Anytime he sees a crease, he can cut upfield, but on this play Shady sprinted to the edge and found daylight to the tune of a 30-yard gain.

Outside-zone runs take longer to develop, which implies they can be blown up more easily than the north-south inside plays. But Kelly will stick with these stretch zone runs, knowing McCoy is just waiting for his chance to flaunt his insane quickness on a big gainer.

Why it's unstoppable: Unstoppable plays always start with the skill of the highlighted player, and McCoy is the NFL's quickest RB, bar none. In particular, the stretch zone suits McCoy so well because it affords him the opportunity to glide toward the sideline and observe how the defense reacts, then put thought into action when he sees daylight by changing direction and accelerating to top speed.

The biggest defensive danger here is over-pursuit. It isn't difficult for linebackers and safeties to sniff these plays out as a variety of sweep, and their instinct is to beat blockers to the point and try to meet Shady at the spot he appears to be heading. If the defense is too aggressive, of course, Shady will simply cut back to the vacant lane. Yet, if the defense isn't aggressive enough, McCoy runs around the edge, as he did in the play I highlighted above. In Week 1, the Eagles suffered a couple of significant injuries on their offensive line, and they might have to start journeyman Andrew Gardner at right tackle Sunday. If that happens, we'll get a look at how unstoppable this scheme really is. (Or the Eagles will simply do nothing but run left ...)

[/h][h=3]1. Peyton Manning's audible option[/h][h=1]The 2013 Broncos boasted the most prolific offense in NFL history, setting single-season records for the most points, most passing yards and most passing TDs. There is, of course, a nearly infinite number of formation and route combinations that the Sheriff is able to process quicker than any man alive, and that means he can get away with subpar arm strength here in his NFL dotage. He's smart enough to conquer your army with a popgun.

The "play" I'm talking about here isn't as much a single route combination as a series of reads whereby Manning diagnoses a defense's plan before it can begin. His legendary pre-snap routine no doubt contains much jabberwocky, but he also signals which option he wants each receiver to enact. Manning's decision-making tree isn't immensely complicated. Speaking very generally, it goes like this:

• If the defense indicates it will fall into Cover 2, he'll ask Julius Thomas or one of his outside receivers to run a cross or sit down between zone defenders in the middle.

• If the defense shows Cover 3 or another single-safety-high defense (such as Cover 1 or Cover 1 robber), he's likely to call for vertical routes and play-action, to catch the back seven cheating forward and loop a throw, especially to the deep corners.

• If the defense plays its corners off, he'll check to a bubble or tunnel screen.

• If the defense shows straight man, someone is going deep.

Of course, these rules aren't absolute, plus this is pretty much the blueprint by which most veteran pocket QBs live. But Manning is able to orchestrate these reactive options out of any play called in the huddle, and what's most amazing is how often he's right:

Here, in a play from last season, Manning sees something in linebacker Joe Mays' posture that gives away some kind of blitz or swap in responsibility for covering Knowshon Moreno out of the backfield. Manning begins gesturing, changing the play. He knows safety Shiloh Keo will favor the inside at the snap, seeking to replace Mays by helping with Jacob Tamme in the slot. This leaves Eric Decker one-on-one on an in-breaking route versus Brice McCain, which Manning knows Decker can win. He communicates this option to Decker, then fires the slant for a TD. He knew what he'd have before the ball even snapped, apparently because of Mays' posture.

Why it's unstoppable: It's not about the weapons. Yes, it helps that Julius Thomas andDemaryius Thomas, Wes Welker, and Emmanuel Sanders are big-time weapons in the passing game. But watch the tape and you'll see how relatively infrequently a Broncos target has a defender anywhere near him. Manning throws to wide-open receivers more than any other NFL QB, and not only because his guys run good routes. He has simply chosen (and signaled) the right option before the play even begins.

So what did the Seahawks do in the Super Bowl? They didn't really scheme Manning. They mostly played a single safety high and zoned the Broncos, didn't blitz much and relied on rotational fronts to pressure Manning enough so his preferred deep routes didn't have time to develop. Against a Seattle zone filled with incredibly athletic linebackers and safeties who "spot-dropped" to prescribed locales to clog the deep and intermediate middle, Manning hit some short passes but then got out of sorts, and as the scoreboard got lopsided, he forced a few poor throws. Most defenses simply don't have the personnel to pull this off, which is why Manning will continue to be an audible-option machine in '14.

[/h]